De grens

tussen de VS en Mexico is voor deze oorspronkelijke volkeren een denkbeeldige,

een grens getrokken door de witte kolonisten en hun nazaten, die deze volkeren met een genocide voor

een groot deel hebben uitgemoord....... De stamverbanden in het zuiden

van de VS en het noorden van Mexico gaan ver over beide grenzen.....

Voor hun

ceremonies zijn de mensen van deze volkeren aangewezen op stammen die over de grens leven en een groot aantal van deze mensen zijn zelfs voor de eerste levensbehoeften aangewezen op winkels over de grens.... Zo is een

bepaald deel van een stam in Mexico voor de boodschappen afhankelijk

van de dichtstbijzijnde plaats, in de VS...... Een veeboer van de O'odham nation moet voor het water dat hij nodig heeft, normaal gesproken op gezichtsafstand, nu mijlen ver omrijden om daar bij te kunnen....... (hetzelfde maken Palestijnen mee op de illegaal door Israël bezette West Bank, hoewel bijvoorbeeld veel boeren daar hun land in het geheel niet meer kunnen bereiken......)

Bij de

grensovergangen worden deze mensen niet zelden getreiterd door

grenswachten en het is altijd weer afwachten of ze wel doorgelaten

zullen worden, zo twijfelt dit leeghoofdige psychopathische geteisem

aan het feit of ze wel echt tot een stam van 'indianen' behoren en

moeten ze dit aantonen door in hun eigen taal te spreken, of zelfs te

zingen, bij weigering kunnen ze worden geweigerd.......

Zoals

gezegd de witte kolonisten hebben deze oorspronkelijke volkeren bijna

uitgemoord (in heel Amerika, de grootste genocide ooit....) en nog

dagelijks worden deze mensen op alle mogelijke manieren dwars

gezeten, neem ook de aanleg van oliepijpleidingen, die op zeker gaan lekken door rivieren en over voor deze mensen heilige

gronden...... (een paar van die enorme en lange leidingen lekken al en dat binnen een jaar na in gebruik te zijn genomen.....)

Kortom de VS, de grootste terreurentiteit op onze kleine aarde, oefent niet

alleen grootschalige terreur uit in verre landen, maar ook in eigen

land, want een dergelijke behandeling, als bij de Israëlische

blokkades op door hen illegaal bezette West Bank, kan je niet anders

dan als terreur zien.......

Het hieronder opgenomen artikel nam ik over van Anti-Media, de foto's komen van The Conversation:

Het hieronder opgenomen artikel nam ik over van Anti-Media, de foto's komen van The Conversation:

For Native Americans, US-Mexico Border is an Imaginary Line

March

19, 2019 at 8:09 pm

Written

by Christina Leza, The

Conversation

(CONVERSATION) — Immigration

restrictions were making life difficult for Native Americans who live

along – and across – the U.S.-Mexico border even before President

Donald Trump declared

a national emergency to

build his border wall.

The

traditional homelands of 36 federally

recognized tribes –

including the Kumeyaay, Pai, Cocopah, O’odham, Yaqui, Apache and

Kickapoo peoples – were split in two by the 1848

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and

1853 Gadsden

Purchase,

which carved modern-day California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas out

of northern Mexico.

Today,

tens of thousands of people belonging to U.S. Native tribes live in

the Mexican states of Baja

California, Sonora, Coahuila and Chihuahua,

my research estimates. The Mexican government does not recognize

indigenous peoples in Mexico as nations as the U.S. does, so there is

no enrollment system there.

Still,

many Native people in Mexico routinely cross the U.S.-Mexico border

to participate in cultural events, visit religious sites, attend

burials, go to school or visit family. Like other “non-resident

aliens,” they must pass through rigorous

security checkpoints,

where they are subject to interrogation, inspection and rejection

or delay.

Many

Native Americans I’ve interviewed for anthropological

research on indigenous activism call

the U.S.-Mexico border “the imaginary line” – an invisible

boundary created by colonial powers that claim

sovereign indigenous territories as

their own.

A border

wall would further separate Native peoples from

friends, relatives and tribal resources that span the U.S.-Mexico

border.

Homelands divided

Tribal

members say that many Native Americans in the U.S. feel detached from

their relatives in Mexico.

“The

effect of a wall is already in us,” Mike Wilson, a member of the

Tohono O’odham Nation, who lives in Tucson, Arizona, told me. “It

already divides us.”

The

Tohono O’odham are among the U.S. federal tribes fighting

the government’s efforts to

beef up existing security with a border wall. In late January, the

Tohono O’odham, Pascua Yaqui and National Congress of Indian

Americans met to

create a proposal for facilitating indigenous border crossing.

The

Tohono O’odham already know how life changes when traditional lands

are physically partitioned.

Verlon Jose, vice-chairman of the Tohono O'odham Nation, at the border barrier that traverses the Tohono O'odham reservation in Chukut Kuk, Ariz., in 2017. Reuters/Rick Wilking

By U.S. law, enrolled Tohono O’odham members in Mexico are eligible to receive educational and medical services in Tohono O’odham lands in the U.S.

That

has become difficult since 2006, when a steel

vehicle barrier was

built along most of the 62-mile stretch of U.S.-Mexico border that

bisects the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Previously,

to get to the U.S. side of Tohono O’odham territory, many tribe

members would simply drive across their land. Now, they must travel

long distances to official ports of entry.

One

Tohono O’odham rancher told The New York Times in 2017 that he must

travel several miles to draw

water from a well 100 yards away from his home –

but in Mexico.

And

Pacific Standard magazine reported in

February 2019 that three Tohono O’odham villages in Sonora, Mexico,

had been cut off from their nearest food supply, which was in the

U.S.

Native rights

Several

international agreements – including the United

Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples –

confirm these communities’ innate rights to draw

on cultural and natural resources across

international borders.

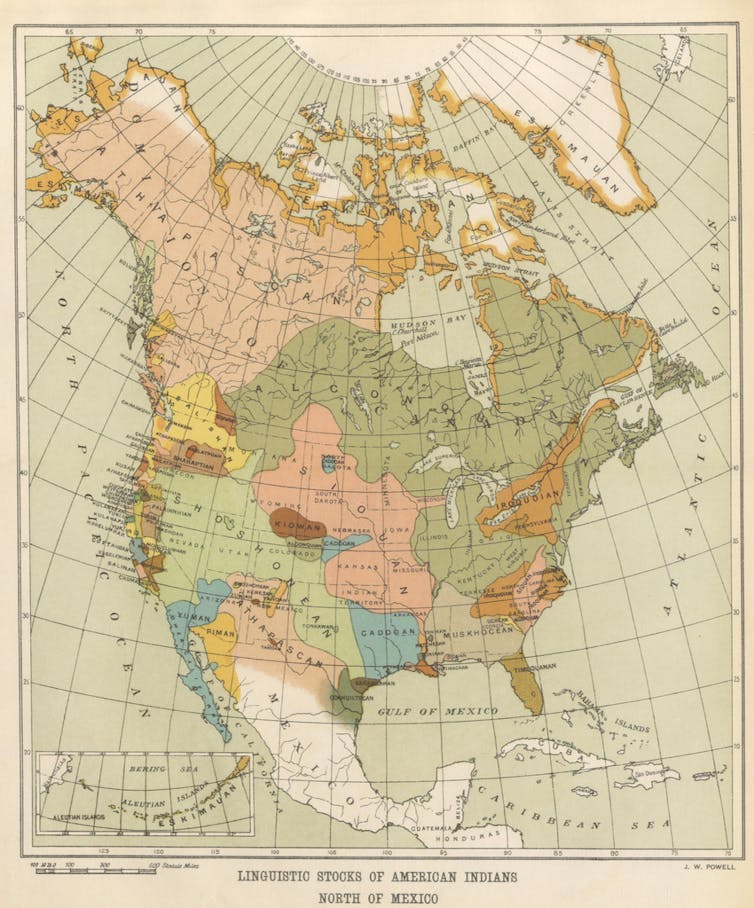

An

1894 map of indigenous North American languages shows how Native

homelands span modern-day national borders. British

Library (jammer overigens dat men niet eenzelfde kaart opnam voor Mexico)

The United States offers few such protections.

Officially,

various federal laws and treaties affirm the rights of federally

recognized tribes to cross between the U.S., Mexico and Canada.

The Jay

Treaty of 1794 grants

indigenous peoples on the U.S.-Canada border the right to freely pass

and repass the border. It also gives Canadian-born indigenous persons

the right to live and work in the United States.

The American

Indian Religious Freedom Act of

1978 says that the U.S. will protect and preserve Native American

religious rights, including “access to sacred sites” and

“possession of sacred objects.” And the 1990 Native

American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act protects

Native American human remains, burial sites and sacred objects.

United

States law also requires that federally recognized sovereign tribal

nations on the U.S.-Mexico border must be consulted

in federal border enforcement planning.

In

practice, however, the free passage of Native people who live across

both the United States’ northern or southern border is curtailed

by strict

identification laws.

The

United States requires anyone entering the country to present a

passport or other U.S.-approved identification confirming their

citizenship or authorization to enter. The Real ID Act of 2005 allows

the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) secretary to waive any U.S. law –

including those protecting indigenous rights – that may

impede border

enforcement.

Several

standard U.S. tribal identification documents – including Form

I-872 American Indian Card and

enhanced tribal photo identification cards – are approved

travel documents that

enable Native Americans to enter the U.S. at land ports of entry.

Arbitrary identity tests

Only

the American

Indian Card,

which is issued exclusively to members of the Kickapoo tribes,

recognizes indigenous people’s right to cross the border regardless

of citizenship.

According

to the Texas

Band of Kickapoo Act of 1983,

“all members of the Band” – including those who live in Mexico

– are “entitled to freely pass and repass the borders of the

United States and to live and work in the United States.”

The

majority of indigenous Mexicans wishing to live or work in the United

States, however, must apply

for immigrant residence and work authorization like

any other person born outside of the U.S. The relevant tribal

governments in the U.S. may also work with Customs and Border Patrol

to waive certain travel document requirements on a case-by-case basis

for short-term visits of Native members from Mexico.

Since

border patrol agents have expansive discretionary

power to

refuse or delay entries in the interest of national security, its

officers sometimes make arbitrary requests to verify Native identity

in these cases.

Such

tests, my research shows, have included asking people to speak their

indigenous language or – if the person is crossing to participate

in a Native ceremony – to perform a traditional song or dance.

Those who refuse these requests may

be denied entry.

Border

agents at both the Mexico and Canada

borders have

also reportedly mishandled or destroyed Native ceremonial or

medicinal items they deem suspicious.

“Our

relatives are all considered ‘aliens,’” said the Yaqui elder

and activist José Matus. “[T]hey’re not aliens. … They’re

indigenous to this land.”

“We’ve

been here since time immemorial,” he added.