Wie een

klein beetje de economie van kolonisators in het verleden onder de

loep heeft genomen, weet dat men nooit een kolonie had behouden, als

daar niet dik geld aan te verdienen was, met uitzondering van strategisch belangrijke gebieden voor die kolonisators, neem Gibraltar....

Onderzoek

van Utsa Patnaik, gepubliceerd op Columbia University Press, toont

dan ook het tegendeel aan van het sprookje dat India de Britse

kolonisator alleen maar geld heeft gekost. Integendeel: GB heeft bij

elkaar 45 biljoen dollar gestolen van de Indiase bevolking, dit in

de periode van 1765 tot 1938. Die 45 biljoen is overigens 17 keer het

huidige Bruto Binnenlands Product van GB......

Via een

smerige systeem wist GB haar winsten zo groot mogelijk te maken: in

1765 nam de East India Company (EIC) de handel over in India, tot die

tijd betaalde GB netjes in zilver voor de producten, echter kort na

die overname van de handel door de EIC, voerde men belastingen in en

van één derde van die belastingopbrengsten uit India, werden de goederen gekocht in

India, ofwel GB kreeg de producten vanaf die tijd gratis, immers de

bevolking betaalde zelf voor die producten via de belastingen........

Na import in GB, exporteerde GB een deel van die goederen naar de rest van Europa, daarmee kon GB de benodigde goederen betalen die nodig waren voor de industrialisatie, zoals staal.... Ofwel GB verkocht in feite gestolen goederen en dat voor een fikse prijs, anders gezegd: dubbele winsten van elk 100%.....

Na import in GB, exporteerde GB een deel van die goederen naar de rest van Europa, daarmee kon GB de benodigde goederen betalen die nodig waren voor de industrialisatie, zoals staal.... Ofwel GB verkocht in feite gestolen goederen en dat voor een fikse prijs, anders gezegd: dubbele winsten van elk 100%.....

Middels de

belastingen die in India werden geroofd, bekostigde GB ook haar

koloniale oorlogen, zoals die tegen China, bovendien werd uit die belasting zoals gezegd de

industrialisatie van GB en haar kolonies Canada en Australië

betaald..... Niet de stoommachine maakte GB groot maar het gestolen

geld van de Indiase bevolking!

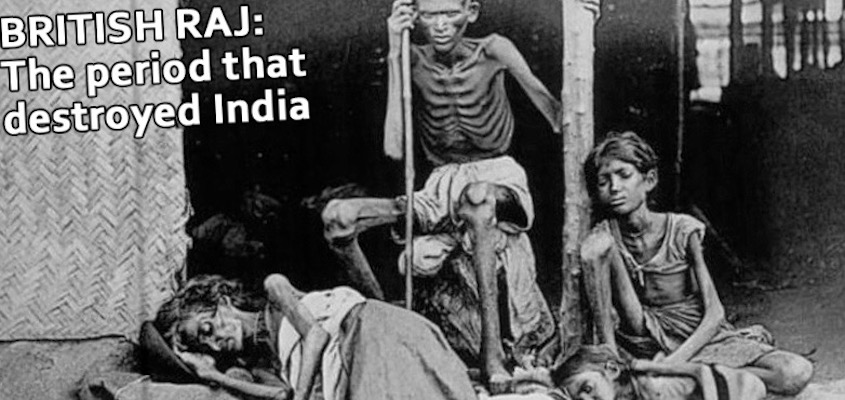

Van 1870

tot 1920 heeft GB met opzet een hongersnood veroorzaakt in India* die aan

tientallen miljoenen Indiërs het leven heeft gekost, ofwel deze

mensen werden vermoord middels één van de ergste oorlogsmisdaden, om

niet te zeggen een grove misdaad tegen de menselijkheid: het uithongeren van een bevolking.......... (zie de foto in het hieronder opgenomen artikel)

Uiteraard

heeft ook GB als Nederland voor het Indonesische volk, niet haar excuses aangeboden aan het volk

van India voor de vreselijke misdaden en uitbuiting, laat staan dat

het herstelbetalingen heeft gedaan........

Het

volgende artikel komt van Black Agenda Report, eerder gepubliceerd op Al Jazeera en Information Clearing House (voor links naar die webpagina's, zie onderaan in het volgende artikel):

How

Britain Stole $45 Trillion From India And Lied About It

Jason

Hickelby 09

Jan 2019

British

colonizers turned a scam for defrauding peasants into a parasitical

relationship that made England rich and impoverished a

subcontinent.

“$45

trillion is 17 times more than the total annual gross domestic

product of the United Kingdom today.”

There

is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonization

of India --

as horrible as it may have been -- was not of any major economic

benefit to Britain itself. If anything, the administration of India

was a cost to Britain. So the fact that the empire was sustained for

so long -- the story goes -- was a gesture of Britain's benevolence.

New

research by the renowned economist Utsa Patnaik -- just published by

Columbia University Press -- deals a crushing blow to this narrative.

Drawing on nearly two centuries of detailed data on tax and trade,

Patnaik calculated that Britain drained a total of nearly $45

trillion from India during the period 1765 to 1938.

It's

a staggering sum. For perspective, $45 trillion is 17 times more than

the total annual gross domestic product of the United

Kingdom today.

How

did this come about?

It

happened through the trade system. Prior to the colonial period,

Britain bought goods like textiles and rice from Indian producers and

paid for them in the normal way -- mostly with silver -- as they did

with any other country. But something changed in 1765, shortly after

the East India Company took control of the subcontinent and

established a monopoly over Indian trade.

“The

re-export system allowed Britain to finance a flow of imports from

Europe which were essential to Britain's industrialization.”

Here's

how it worked. The East India Company began collecting taxes in

India, and then cleverly used a portion of those revenues (about a

third) to

fund the purchase of Indian goods for British use. In other words,

instead of paying for Indian goods out of their own pocket, British

traders acquired them for free, "buying" from peasants and

weavers using money that had just been taken from them.

It

was a scam -- theft on a grand scale. Yet most Indians were unaware

of what was going on because the agent who collected the taxes was

not the same as the one who showed up to buy their goods. Had it been

the same person, they surely would have smelled a rat.

Some

of the stolen goods were consumed in Britain, and the rest were

re-exported elsewhere. The re-export system allowed Britain to

finance a flow of imports from Europe, including strategic materials

like iron, tar and timber, which were essential to Britain's

industrialization. Indeed, the Industrial Revolution depended in

large part on this systematic theft from India.

On

top of this, the British were able to sell the stolen goods to other

countries for much more than they "bought" them for in the

first place, pocketing not only 100 percent of the original value of

the goods but also the markup.

After

the British Raj took over in 1847, colonizers added a special new

twist to the tax-and-buy system. As the East India Company's monopoly

broke down, Indian producers were allowed to export their goods

directly to other countries. But Britain made sure that the payments

for those goods nonetheless ended up in London.

“The

Industrial Revolution depended in large part on this systematic theft

from India.”

How

did this work? Basically, anyone who wanted to buy goods from India

would do so using special Council Bills -- a unique paper currency

issued only by the British Crown. And the only way to get those bills

was to buy them from London with gold or silver. So traders would pay

London in gold to get the bills, and then use the bills to pay Indian

producers. When Indians cashed the bills in at the local colonial

office, they were "paid" in rupees out of tax revenues --

money that had just been collected from them. So, once again, they

were not in fact paid at all; they were defrauded.

Meanwhile,

London ended up with all of the gold and silver that should have gone

directly to the Indians in exchange for their exports.

This

corrupt system meant that even while India was running an impressive

trade surplus with the rest of the world -- a surplus that lasted for

three decades in the early 20th century -- it showed up as a deficit

in the national accounts because the real income from India's exports

was appropriated in

its entirety by Britain.

Some

point to this fictional "deficit" as evidence that India

was a liability to Britain. But exactly the opposite is true. Britain

intercepted enormous quantities of income that rightly belonged to

Indian producers. India was the goose that laid the golden egg.

Meanwhile, the "deficit" meant that India had no option but

to borrow from Britain to finance its imports. So the entire Indian

population was forced into completely unnecessary debt to their

colonial overlords, further cementing British control.

“London

ended up with all of the gold and silver that should have gone

directly to the Indians.”

Britain

used the windfall from this fraudulent system to fuel the engines of

imperial violence -- funding the invasion of China in

the 1840s and the suppression of the Indian Rebellion in 1857. And

this was on top of what the Crown took directly from Indian taxpayers

to pay for its wars. As Patnaik points out, "the cost of all

Britain's wars of conquest outside Indian borders were charged always

wholly or mainly to Indian revenues."

And

that's not all. Britain used this flow of tribute from India to

finance the expansion of capitalism in Europe and regions of European

settlement, like Canada and Australia. So not only the

industrialization of Britain but also the industrialization of much

of the Western world was facilitated by extraction from the colonies.

Patnaik

identifies four distinct economic periods in colonial India from 1765

to 1938, calculates the extraction for each, and then compounds at a

modest rate of interest (about 5 percent, which is lower than the

market rate) from the middle of each period to the present. Adding it

all up, she finds that the total drain amounts to $44.6 trillion.

This figure is conservative, she says, and does not include the debts

that Britain imposed on India during the Raj.

These

are eye-watering sums. But the true costs of this drain cannot be

calculated. If India had been able to invest its own tax revenues and

foreign exchange earnings in development - as Japan did

- there's no telling how history might have turned out differently.

India could very well have become an economic powerhouse. Centuries

of poverty and suffering could have been prevented.

“The

cost of all Britain's wars of conquest outside Indian borders were

charged always wholly or mainly to Indian revenues."

All

of this is a sobering antidote to the rosy narrative promoted by

certain powerful voices in Britain. The conservative historian Niall

Ferguson has claimed that British rule helped "develop"

India. While he was prime minister, David Cameron asserted that

British rule was a net help to India.

This

narrative has found considerable traction in the popular imagination:

according to a 2014 YouGov poll, 50 percent of people in Britain

believe that colonialism was beneficial to the colonies.

Yet

during the entire 200-year history of British rule in India, there

was almost no increase in per capita income. In fact, during the last

half of the 19th century - the heyday of British intervention --

income in India collapsed by half. The average life expectancy of

Indians dropped by a fifth from 1870 to 1920. Tens of millions died

needlessly of policy-induced famine.

Britain

didn't develop India. Quite the contrary -- as Patnaik's work makes

clear -- India developed Britain.

What

does this require of Britain today? An apology? Absolutely.

Reparations? Perhaps -- although there is not enough money in all of

Britain to cover the sums that Patnaik identifies. In the meantime,

we can start by setting the story straight. We need to recognize that

Britain retained control of India not out of benevolence but for the

sake of plunder and that Britain's industrial rise didn't emerge sui

generis from the steam engine and strong institutions, as our

schoolbooks would have it, but depended on violent theft from other

lands and other peoples.

COMMENTS?

Please

join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at

http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or,

you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com

===================================* India dat destijds veel groter was, dus inclusief: Pakistan, Oost-Pakistan dat nu Bangladesh wordt genoemd en Ceylon, nu Sri Lanka genaamd.