(On the top right hand side of this page you can choose for a translation in the language of your choice in Google Translate)

Het kan je bijna niet zijn ontgaan dat de VS en Israël afgelopen zaterdag weer een oorlog zijn begonnen tegen Iran en niet andersom, zoals je uit de woorden van premier Rob Jetten (D666) zou kunnen begrijpen..... Jetten zei afgelopen zaterdag dat Iran de grote destabiliserende factor is in het Midden-Oosten.... Zo onzinnig dat je je kapot zou kunnen lachten als de situatie niet zo ernstig was..... Alsof tot 2 keer toe een oorlog beginnen tegen Iran geen destabiliserende factor is, om over alle andere illegaal door de VS en Israël begonnen oorlogen nog maar te zwijgen....

'At least 153 dead after reported strike on school, Iran says' Een artikel van de BBC

'At least 153 dead after reported strike on school, Iran says' Een artikel van de BBC

Ach, Jetten is blijkbaar vergeten dat Israël en de VS vorig jaar al evenzo een oorlog zijn begonnen tegen Iran. maar ja 'Rob' had en heeft het druk natuurlijk, daarnaast moet hij regelmatig op vakantie en kan zomaar van alles zijn ontgaan....

Zo zal het Jetten niet zijn opgevallen dat de fascistische terreurstaat Israël afgelopen jaar naast Iran nog 4 andere landen in het Midden-Oosten heeft aangevallen...... Dat Israël nu al ruim 2 jaar lang een genocide uitvoert op de Palestijnen in de Gazastrook was Jetten (wonderlijk genoeg) wel opgevallen, hij stelde zelfs dat Israël met de genocide een rode lijn had overschreden.... Nu hij als premier medeverantwoordelijk is voor het handelen van Nederland op gebied van het buitenlandbeleid is 'onze' Jetten die woorden vergeten.....

Hier de reactie van VVD kwaadaardigheid Yeşilgöz op de illegaal begonnen oorlog tegen Iran, overgenomen van het Noordhollands Dagblad:

Yeşilgöz: veiligheid militairen in regio heeft hoogste prioriteit

De veiligheid van Nederlandse militairen in het Midden-Oosten heeft de „hoogste prioriteit”, laat minister Dilan Yeşilgöz van Defensie weten. Het aantal Nederlandse militairen in de regio is beperkt. Ze zijn onder meer voor missies in Irak, Israël en de Golfstaten.

Defensie volgt de situatie volgens de bewindsvrouw nauwlettend nadat Israël en de Verenigde Staten waren begonnen met de aanval op Iran. Zij roept net als andere leden van het kabinet op tot terughoudendheid en het voorkomen van verdere escalatie. „Stabiliteit in de regio is essentieel.”

Ja hè Yeşilgöz, de stabiliteit in de regio is essentieel, vooral als het om 'agressie van Iran' gaat, vandaar dat ze deze illegaal begonnen oorlog niet in alle toonaarden veroordeelt, maar stelt dat verdere escalatie voorkomen moet worden.... Wat bedoelt hare helleveegheid daarmee, dat Israël geen kernwapens moet inzetten??

Uh Yeşilgöz, hoe dat zo: Nederlandse troepen op missie in Israël? Om daar ervaringen op te doen hoe een genocide uit te voeren, hoe gevangenen te martelen en te verkrachten, of hoe keer op keer illegale oorlogen te beginnen??!!! Toch al schandelijk dat Nederlandse troepen aanwezig zijn in Irak, nadat 'ons leger' in opdracht van opvolgende regeringen en de grote VS terreurleider dat land mede naar de kloten heeft geholpen?? Ook de aanwezigheid in de Golfstaten is misselijkmakend, wat moet ons leger in deze dictatoriaal geregeerde staten, leren hoe je de bevolking er met geweld onder moet houden?? En hoe de genocide in Soedan te helpen?? (de NOS schrijft dit tegenwoordig als 'Sudan', blijkbaar vindt men daar nu dat men in het verleden 'wel eens fout heeft bericht' over dat land toen men het nog schreef als Soedan....

VVD'er Brekelmans (what's in a name?) moest ook nog even van zich laten horen:

De operatie komt niet onverwachts, laat VVD-fractievoorzitter Ruben Brekelmans op X weten. „De veiligheid van onschuldige burgers, Nederlanders daar en in de regio, en het voorkomen van verdere escalatie in de regio zijn nu belangrijker dan ooit.”

Ook jij hè Brekelmans >> onschuldige burgers en vooral Nederlanders mogen niet lijden onder de terreuroorlog die Israël en de VS zijn begonnen, maar je weet donders goed dat dit niet is te voorkomen, precisiebombardementen bestaan niet hoe lang men die leugen ook heeft gekoesterd in het westen, een leugen was het en een leugen blijft het!! Bij de VPRO gistermorgen (op NPO Rado1) de zeer 'deskundige' Wijninga van het HCSS (opgeleid tot grootlobbyist van de wapenmaffia in de VS) die stelde dat de raket op een meisjesschool een foutje was, dat kan volgens deze multi-keuteldraaier gebeuren met 'precisiewapens.....' (HCSS >> 'Haags Centrum Strategische Studies', een ordinaire lobbyclub voor terreurorganisatie NAVO, de VS en de wapenmaffia)

Hier de reactie van het ChristenUnie (CU) keffertje Bikker:

„In deze spannende dagen leven we mee met het dappere Iraanse volk dat met bruut geweld onderdrukt wordt door de ayatollahs”, twittert Mirjam Bikker (ChristenUnie).

Spannende dagen mevrouw Bikker?? Walgelijke dagen met alweer een illegaal begonnen oorlog door Israël en haar grote beschermer, de grootste terreurentiteit ter wereld de VS!! Dat er burgers zijn vermoord in deze illegale oorlog van de VS en Israël is voor haar blijkbaar 'collateral damage...' De VS en Israël hebben deze eeuw heel wat meer geweld gebruikt dan Iran, neem alleen al de illegaal gevoerde oorlogen van de VS (met hulp van haar slaafse NAVO-bondgenoten, waaronder Nederland mevrouw Bikker!!), die hebben aan meer dan 5 miljoen mensen het leven gekost!! Om nog maar te zwijgen over de illegaal opgelegde VS-sancties aan meerdere landen (vrijwel altijd gesteund door andere westerse landen, waaronder Nederland mevrouw Bikker!!), die aan een paar honderdduizend mensen, waaronder een groot aantal kinderen, het leven hebben gekost, ofwel die in feite werden vermoord middels deze smerige vorm van oorlogsvoering..... En dat Israël al meer dan 2 jaar lang een genocide uitvoert op de Palestijnen, wel daarvan kan mevrouw Bikker echt niet wakker liggen, immers die officieel meer dan 70.000 vermoorde Palestijnen (in werkelijkheid zal later blijken dat het om hoogstwaarschijnlijk 10 keer zoveel vermoorde Palestijnen gaat) >> Israël mag doen wat het wil van mevrouw Bikker, hoeveel kinderen er zich ook bevinden onder de vermoorde en voor het leven verminkte slachtoffers......*

Uiteraard wil een meerderheid van de Nederlandse politici niet dat er gewonde Palestijnse baby's worden geholpen in Nederlandse ziekenhuizen >> veronderstel!! Het overgrote deel van al de hiervoor aangehaalde door de VS en Israël vermoorden waren dan ook vooral vermoorde moslims en dat interesseert het joods/christelijk Nederland in het geheel niet, opvallend overigens dat de CU wel voor hulp aan deze kinderen heeft gekozen. (jammer dat de grof-inhumane politici die tegenstemden waaronder de SGP niet weten dat zich onder de Palestijnen veel mensen bevinden die meer joodse genen hebben dan de 'officiële Joden' in Israël, wat moet hun bedachte god daar 'wel niet' van vinden als zij voor diens troon staat??)

Het voorgaande geldt zo mogelijk nog meer voor de onbeschofte opmerking ten aanzien van moslims door SGP christenbroeder van Dijk:

„Niet onverwacht, maar toch ingrijpend”, noemt Diederik van Dijk (SGP) de operatie. „Hopelijk mag het leiden tot vrijheid voor de Iraanse burgers en een einde maken aan die gruwelijke islamitische terreur die de wereld zo lang heeft geteisterd.”

Gruwelijke 'islamitische terreur?' Van Dijk >> hoe noem jij de genocide op de Palestijnen dan? Oh ja, die ontken je gewoon, ook al kan je je scheelkijken aan de video's op het internet, die aangeven hoe gruwelijk de genocidale terreur van het Israëlische leger (IDF) ook is en al gaf datzelfde leger in eerste instantie aan het eens te zijn met het aantal van meer dan 70.000 vermoorde Palestijnen (al zal het IDF het woord 'vermoord' nooit gebruiken voor de door haar gedode Palestijnen) Of wat denk jij van Dijk van het verkrachten van Palestijnse meisjes, jongens, vrouwen en mannen in de concentratiekampen van het IDF, of noem jij dat geen terreur?? En nee ik zal het woord 'joodse terreur' nooit gebruiken van Dijk....)

Wat de nieuwe minister van Defensie laat weten kan ook al niet door de 'internationale beugel':

Na de aanval op Iran roept „Nederland alle partijen op om terughoudendheid te betrachten en verdere escalatie te voorkomen”, laat minister Tom Berendsen (Buitenlandse Zaken, CDA) in een reactie aan het ANP weten. „Stabiliteit in de regio is essentieel.” Hij laat verder weten dat het kabinet de situatie in Iran, Israël en de bredere regio nauwgezet volgt en in contact staat met de ambassades in de regio.

Na de aanval iedereen oproepen om terughoudendheid te betrachten?? Zo van Iran, hier spreekt jullie Nederlandse minister van Defensie en dat jullie binnen een jaar tijd twee keer zwaar zijn gebombardeerd betekent alles behalve dat jullie terug mogen slaan, jullie moeten verdere escalatie tegengaan.... Benieuwd of hij zijn Israëlische collega, de fascistisch genocidale Katz, al heeft gebeld om de blijvende Nederlandse steun toe te zeggen, het zal me niet verbazen >> integendeel.... Hoe het mogelijk dat deze politici en anderen de illegale oorlog tegen Iran niet in alle toonaarden hebben veroordeeld?? SCHANDE!!!

Opvallend dat alleen SP'er Dobbe en DENK-leider van Baarle de begonnen illegale oorlog veroordelen en het het kabinet oproepen hetzelfde te doen, zoals het internationale recht inderdaad voorschrijft:

Sarah Dobbe (SP) spreekt van een aanval op het internationaal recht, „wat je ook vindt van het regime in Iran”. Zij vindt net als DENK-leider Stephan van Baarle dat het kabinet de aanval moet veroordelen. „Netanyahu en Trump storten het Midden-Oosten opnieuw in oorlog, terwijl onderhandelingen plaatsvonden”, aldus Van Baarle.

Het overgrote deel van de Nederlandse en andere westerse politici moeten zich kapot schamen dat ze accepteren dat er zo schunnig wordt omgegaan met internationale wet- en regelgeving, zoals eerder gezien met de piraterij van de VS (en andere westerse landen zoals België dat gisteren een tanker van de zogenaamde Russische schaduwvloot van zee kaapte) en de enorme terreuraanval op het soevereine land Venezuela, waarbij het ongelofelijke terreurbewind in Washington zelfs de democratisch gekozen president en diens vrouw lieten ontvoeren, om nog maar te zwijgen over het verwurgen van de Cubaanse bevolking met de totale boycot op de aanvoer van olie en de nu al meer dan 60 jaar durende sancties tegen dat land.....** (sancties tegen Iran werden ingesteld vanaf 1979, verscherpt door oorlogsmisdadiger, hoogstwaarschijnlijk pedo en cigar-man Clinton in 1995) Hetzelfde geldt voor het zwijgen over de Israëlische genocide op de Palestijnen, die aan zo enorm veel mensen het leven heeft gekost, een genocide die nog steeds doorgaat, maar die het westen amper of niet ongerust maakt, sterker nog het westen blijft onder aanvoering van de VS wapens leveren aan deze fascistisch genocidale apartheidsstaat....

Vergelijk dat eens met de volkomen uitgelokte inval van Rusland in de fascistische dictatuur Oekraïne, waar dezelfde hypocrieten achter nu al het 20ste sanctiepakket tegen dat land staan, terwijl die aanval als gezegd werd uitgelokt en niet in de schaduw kan staan van de westerse terreur deze eeuw met de gevoerde illegale oorlogen, noch met de genocide die Israël uitvoert op de Palestijnen, noch met de illegaal opgelegde westerse sancties aan meerdere landen (waar de SP zich jammer genoeg ook heeft uitgesproken tegen Rusland, uit angst nog meer kiezers te verliezen, daarmee juist zorgend dat de partij nog meer steun heeft verloren....) De VS stelt intussen dat Iran ongeprovoceerd terugslaat, zeg maar hoe zot je het wil hebben >> de VS levert!! Maar ja wat wil je met een fascistisch bestuurd land, waar men de uitspraak van nazi-monster Goebbels eert: als je een leugen maar lang genoeg herhaalt wordt deze vanzelf waarheid (tevens het levensmotto van aartsleugenaar en SG van de NAVO >> Rutte)

Trump stelde eerst dat hij het bewind in Teheran wilde vervangen, wat hij nu weer heeft veranderd vanwege in het platleggen van de zogenaamde wil van Iran een kernwapen te ontwikkelen, een leugen van enorme proporties, die al vanaf de jaren 80 van de vorige eeuw wordt herhaald, terwijl de VS nota bene overlegde met Iran over deze zaak, werd deze oorlog al gepland, ofwel dat hele overleg was volledig show.... Kortom de VS kan nooit meer worden vertrouwd aan de 'overlegtafel', al was dat voor velen allang duidelijk, iedereen die na gisteren nog aandringt op overleg met de VS in politieke en geopolitieke zaken moet als volidioot worden gezien!!

Iedereen die een beetje oplet zal hebben begrepen dat deze smerige zet van Trump is bedoeld om de aandacht af te leiden van zijn pedoseksuele avonturen die nogmaals aan het licht kwamen door de zaak Epstein!!***

Gisteren zouden de EU-regeringsleiders middels video-verbinding hebben vergaderd over de VS-Israëlische oorlog tegen Iran, ja je kan natuurlijk niet verwachten dat men dit zaterdag al zou hebben gedaan >> de idee alleen all!! Waarschijnlijk naar aanleiding daarvan lieten Jetten en de Duitse minister van buitenlandse zaken Wadephul niet weten dat de VS en Israël hun internationale boekje ver te buiten gaan met hun oorlog tegen Iran, nee deze oorlogshitsers lieten (nog eens) weten dat Iran een gevaar is voor de regio en zelfs voor Europa......

Zoals gewoonlijk doen alle zogenaamd onafhankelijke media, die tegenwoordig bijna volledig eenzijdige berichtgeving brengen, mee aan de anti-Iraanse propaganda, zoals gistermorgen (zondag 1 maart 2026) op de NPO Radio 1 in het uitgebreide NOS Radio1 Journaal en op de VPRO en als de politici kraaien ze victorie van de daken over het vermoorden van leiders in Iran.... (over die daken gesproken >> er zou in Iran sprake zijn geweest van fluitconcerten en gejuich over de de dood van ayatollah Khamenei vanaf de balkons en open ramen, uit wat men liet horen kon ik niets anders opmaken dan dat een halve kip en een paardenkop hier aan meededen).

De reguliere westerse media in handen van enkele spuugrijke figuren, die belang hebben bij een groeiende westerse wapenindustrie, het vernielen van de wereld middels het gebruik van fossiele brandstoffen en het bewaren van de huidige status quo met een groeiende gang naar dictatuur, waar die media zelfs pleiten voor censuur op de sociale media en daarom eenzijdige berichtgeving brengen.... Uiteraard hebben die media als westerse politici zo min mogelijk aandacht voor de moord op meer dan 140 meisjes en andere Iraanse burgers, terwijl ze alarm zouden moeten slaan over deze enorme VS-Israëlische terreur.

De volgende video toegevoegd op 4 maart 2026 (met dank aan voor het delen):

De VS is niets anders dan een vereniging van terreurstaten, die volledig is losgeslagen van elke internationale wet- en regelgeving, een vereniging van terreurstaten die oorlog, dood en vernietiging zaait over de wereld waar het maar uitkomt voor dit fascistische land, waar dit in 'het klein' geldt voor haar partner in oorlogsmisdaden >> de fascistische genocidepleger Israël..... Het westen hoeft dan ook niet vreemd op te kijken als de volgende keer een bevriende staat wordt aangevallen door de VS....

WDR 5 meldde vanmorgen (2 maart 2026) in het nieuws van 10.00 u. dat er intussen meer dan 500 Iraniërs om het leven zijn gekomen >> lees: vermoord middels de enorme terreur van de VS en Israël.... Dit aantal vermoorden werd die middag bijgesteld naar 550....

Toevoeging op 5 maart 2026: het aantal doden door de VS-Israëlische terreuroorlog is volgens Drop Site Daily op 5 maart (na 5 dagen) gestegen tot meer dan 1.200 (ofwel vermoorde mensen), dit middels meer dan 1.300 aanvallen.... Vergeet niet dat er bij oorlog altijd veel meer (ook zwaar) gewonden zijn te betreuren...... Een naar bijkomend effect is het feit dat met die oorlog de aandacht is afgeleid van de genocide op de Palestijnen, alsmede de pedo-avonturen van oorlogsmisdadiger Trump.....

De staatsradiozenders van Nederland (NPO Radio1, plus die van Duitsland) stelden vanmorgen dat Iran meerdere Golfstaten heeft aangevallen, zonder daarbij te vermelden dat men militaire bases van de VS heeft aangevallen, om 10.00 u. meldde WDR 5 dit wel, na eerst hetzelfde te hebben gemeld..... Vanaf 10.00 u. meldde bijvoorbeeld Deutschlandfunk dat ook olieraffinaderijen in buurlanden worden aangevallen, wat er niet bij werd vermeld is dat deze olieraffinaderijen ook benzine en kerosine leveren aan de militaire VS-bases in hun landen (waaronder luchtmachtbases). Het is wel duidelijk dat men met het op deze manier brengen van berichten Iran verder wil demoniseren.... De reguliere westerse media doen hun uiterste best om hun bevolkingen duidelijk te maken dat de illegale oorlog die de VS en Israël zijn begonnen wellicht 'niet geheel in overeenstemming zijn met internationale wet- en regelgeving', maar dat het geheel logisch is dat deze 2 landen Iran aanvallen, zoals eerder opgemerkt onder andere met de valse verdediging dat het Iran is die het Midden-Oosten destabiliseert....

Toevoeging op 3 maart 2026: Deutschlandfunk radio meldt in het nieuws van 12.00 u. dat de Israëlische terreurluchtmacht een belangrijk radiostation heeft uitgeschakeld >> ook dat moet worden gezien als een enorme oorlogsmisdaad, daar een radiostation van groot belang is als een land wordt aangevallen, alleen al om burgers te waarschuwen voor aanvallen, of om bepaalde plekken te mijden vanwege onontplofte bommen (het is vrijwel zeker dat Israël ook nu weer clusterbommen gebruikt, deze fascistisch genocidale staat fabriceert deze munitie nog steeds en verkoopt het ook aan wie het maar wil hebben, behalve dan aan buurlanden zoals je zal begrijpen)

Toevoeging van het volgende LinkdIn bericht op 7 maart 2026:

==============

Toevoeging op 9 maart 2026:

Met een enorme knal viel ik vanmiddag van m'n stoel toen ik een petitie van 'DeGoede Zaak' (een zeer foute naam) onder ogen kreeg, dit keer was aan de naam 'Zonne van' toegevoegd, dus 'Zonne van DeGoedeZaak.....' ha! ha! ha! ha! Hierin vraagt deze enorme dwaze organisatie een petitie te tekenen voor de vrijheid van het Iraanse volk, terwijl dat volk wordt vermoord middels bombardementen door Israel en de VS!! DeGoedeZaak heeft zich voor eeuwig belachelijk gemaakt en kan beter stoppen met haar petities >> te belachelijk voor woorden!!

'Leuk ook' dat wij deels het gelag mogen betalen door de stijging van de olie- en gasprijs (de laatste is intussen met 15% gestegen....).....

---------------------------------------------

Voor de bezoekers die Engels niet kunnen lezen: voor de niet op dit blog gepubliceerde artikelen in het Engels onder de links, moet je zelf even een vertaalapp zoeken op het web. Er zijn gratis apps van redelijke kwaliteit die dit kunnen (soms in 2 of of meer delen >> bij lange artikelen). Af en toe krijg je bij het openen van een nieuwe pagina een pop-up die vraagt of je een vertaling wilt hebben als de bewuste pagina in een andere taal is gesteld.

Visitors who can't read Dutch for the articles other than from this blog: on the web you can find free translation apps with reasonable quality, which can do the job (it's possible you have to do it 2 or more times >> with lengthy articles) Sometimes when you open a new page in an other language, you get a pop-up with the question if you need a translation.

* Zie: 'Palestina en Israël: wat vindt de ChristenUnie?' (14 oktober 2025) Een artikel van The Rights Forum.

---------------------------------------------

** Zie: 'Cuba: VS-terreur >> van blokkade naar verwurging van de bevolking' (5 februari 2026) En zie de links naar meer berichten over VS-terreur tegen Cuba!!

---------------------------------------------

*** Hier links naar berichten waarin schoft Epstein en Israël een rol spelen: 'Epstein Received Sensitive Military Intelligence Amid Gates Foundation Polio Campaign in Pakistan' (28 februari 2026) Een artikel van Waqas Ahmed and Murtaza Hussain, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News. >> Justice Department emails show that Epstein helped the Gates Foundation gain access to the Taliban—and received confidential reports and intelligence on Pakistani military operations.

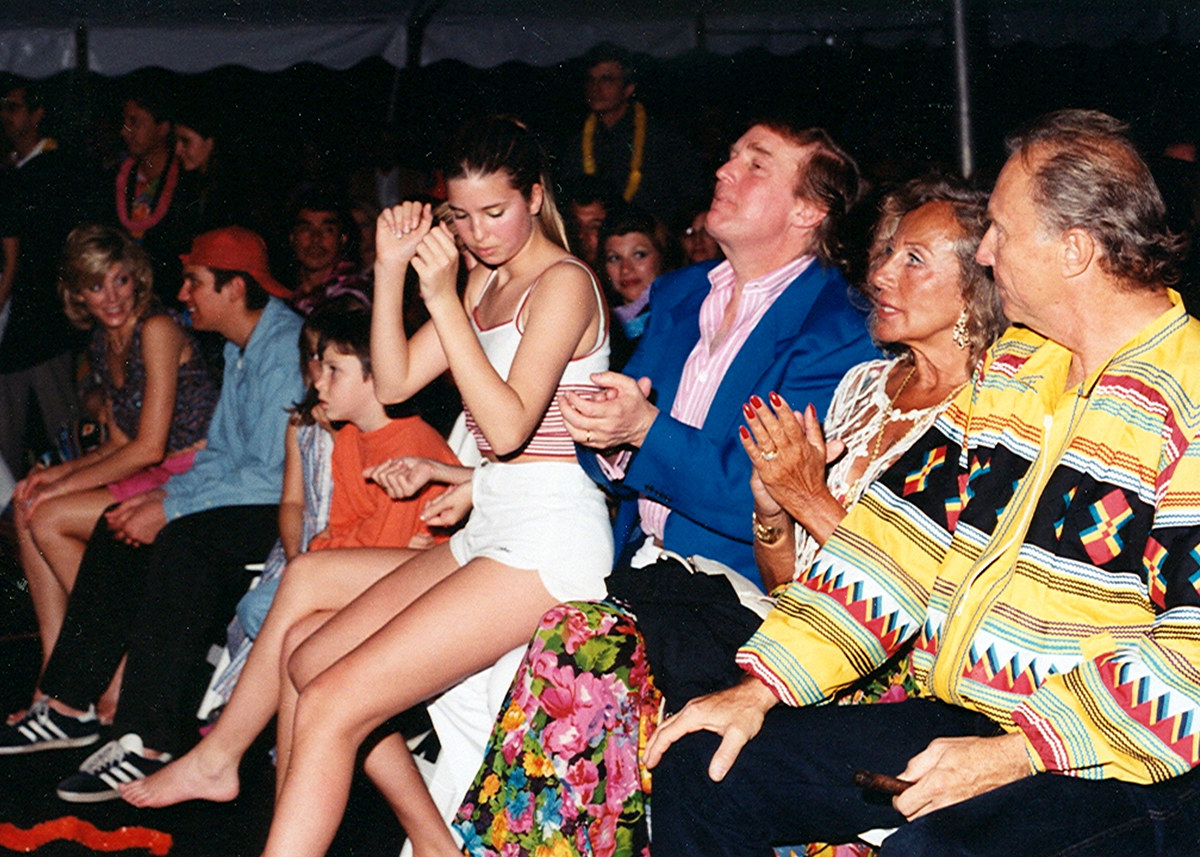

'The missing Epstein files' (26 februari 2026) Een artikel van Judd Legum, gepubliceerd op Judd at Popular Information. Hier een deel van dit artikel, een artikel waarin: pedofiel, fraudeur, belastingontduiker, ordinaire misdadiger, oorlogsmisdadiger, mede-genocidepleger en godbetert president van de VS >> Donald Trump een hoofdrol speelt. >> “We did not protect President Trump.” That is what Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche said on January 30, after what he described as the final release of the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) files on convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. It turns out that was not true. According to a new report by NPR, the DOJ is withholding “more than 50 pages of FBI interviews, as well as notes from conversations with a woman who accused Trump of sexual abuse decades ago when she was a minor.” The New York Times also reported Wednesday that the DOJ withheld summaries of three FBI interviews with the woman about her interactions with Trump. They released a fourth FBI interview, where the woman made allegations about Epstein. The missing files were first discovered by independent journalist Roger Sollenberger. The failure to disclose the interviews about Trump and related files seemingly puts the administration in violation of the Epstein Files Transparency Act. That law, signed by Trump last year, prohibits the withholding or redacting of documents “on the basis of embarrassment, reputational harm, or political sensitivity, including to any government official, public figure, or foreign dignitary.”

'Epstein After Sade' (23 februari 2026) Een artikel van Fabio Vighi, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Under Emergency Capitalism, Spectacles Perform as Symptoms of Systemic Exhaustion. Waar 'kapitalisme' staat in dit artikel kan je wat mij betreft ook 'fascisme' lezen!!

'Not Forgetting the Victims' (19 februari 2026) Een artikel van Binoy Kampmark, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Club Epstein and Crimes Against Humanity.

'The Epstein Scandal: The last chapter of oligarchism — Interview with Ray McGovern' (12 februari 2026) Hier de video:

'The Israeli Government Installed and Maintained Security System at Epstein Apartment' (18 februari 2026) Een artikel van Ryan Grim en Murtaza Hussain, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News >> Security equipment and alarms were installed by the Israeli government at a notorious Manhattan residence frequented by former PM Ehud Barak. Werkelijk niets gaat de genocidale fascistische apartheidsstaat Israël te ver.....

'They Called Rotherham a "Muslim Problem" — What Do They Call Epstein's Island?' (16 februari 2026) Een artikel van Karim, gepubliceerd op BettBeat Media >> Where's "Race" When Discussing the World's Most Notorious Grooming Gang? Hier een klein deel van het artikel >> The release of the Department of Justice files on Jeffrey Epstein has confirmed what the victims always said — that a network of extraordinarily wealthy and powerful men raped children with impunity for many decades, shielded by prosecutors, intelligence agencies, and the velvet machinery of class. The files have given us names, dates, flight logs, and email exchanges so depraved they read like evidence from a civilization in terminal moral collapse. And yet, in the great churning of American media, one dimension of this case remains almost perfectly untouched: race. The Home Office’s own 2020 research review found that group-based child sexual exploitation offenders are “most commonly White.” A 2024 report by the Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse found that where ethnic background was recorded, ninety percent of offenders were white, five percent were Asian, and two percent were Black. The Ministry of Justice’s own prosecution data shows that eighty-eight percent of defendants prosecuted for child sexual abuse offenses in England and Wales were white — a figure that slightly exceeds white representation in the general population. UCL researchers, reviewing the Home Office data, declared that “a powerful modern racial myth has been exploded. What started as a far-right trope had migrated into the mainstream.” The same report admitted that “grooming gangs are not a ‘Muslim problem.’”

'Epstein Flipped Israel’s Gaza-Tested Biometric Scanners Into Nigeria Ports Deal for UAE' (16 februari 2026) Een artikel van Murtaza Hussain and Ryan Grim, gepublicerd op Drop Site News >> Former Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak used the Boko Haram threat to pilot Israeli facial recognition scanning in Nigeria, while Jeffrey Epstein facilitated oil and logistics deals. Onder andere over de banden van Epstein met het Israelische leger en de Verenigde Arabische Emiraten (VAE).

'Noam Chomsky, Jeffrey Epstein and the Politics of Betrayal' (9 februari 2026) Een artikel van Chris Hedges.

'Chris Hedges on Trump, Epstein and the Decline of American Democracy | UpFront' (8 februari 2026) Een video met Chris Hedges, waarin hij o.a. Epstein noemt en de onverschilligheid van machtige figuren die denken overal mee weg te komen (wat meestal ook zo is....) >> A year into Donald Trump’s return to office, a wave of hardline actions - from volatile ICE raids to political pressure on the media - have raised alarms about the expansion of the president's power.

'If You Think Our Rulers Do Bad Things In Secret, Wait Til You See What They Do Out In The Open' (9 februari 2026) Een artikel van Caitlin Johnstone. Hier een passage uit dit artikel >> Pay attention to the Epstein files. Pay attention to what little we can learn about how these freaks conduct themselves behind closed doors. By all means, pay close attention to these things. But don’t forget to also pay attention to the far greater evils they are inflicting in full view of the entire world.

'Lord Mandelson' (6 februari 2026) Een artikel van Julian Vigo, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds. Trapped in the Epstein Web. Hier 2 passages uit dit artikel >> Mandelson’s case is particularly dire. Here was a person who had already lost his job in the cabinet twice over issues involving matters of money and the wealthy. In 1998, he resigned as trade and industry secretary after obtaining a loan of £373,000 from the Paymaster General, Geoffrey Robinson, to purchase a house. In 2001, he fell foul over a passport application from Indian billionaire Srichand Hinduja who had pledged £1m in sponsorship for the Millenium Dome project when Mandelson was in charge. Despite a heavily blotted copybook, Mandelson still secured the confidence of Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer to be appointed ambassador to Washington in anticipation of the second Trump administration. The association between Mandelson and the late Epstein was already known, making the appointment dangerous in the extreme. The publication of certain emails revealing the continuing friendship post-conviction doomed yet another job. Starmer stelde dus na het bekendworden van e.e.a. niet op de hoogte te zijn geweest van de misstappen van deze smerige hufter toen hij hem aanstelde als ambassadeur in Washington, wat alweer genoeg zegt over zijne kwaadaardigheid Starmer......

'The Epstein Files, Buried In Plain Sight' (5 februari 2026) Een artikel van Thomas Karat >> Decoding the Strategy behind the lates file dump. Hier 2 passages uit dit artikel >> Consider the mathematics of the Epstein release through this lens. Three-and-a-half million pages, released with what NPR described as “no sense of organization or context. A professional analyst reading at a rate of fifty pages per hour—fast by any standard—would require 70,000 hours to process this material. That represents thirty-five years of full-time work by a single analyst.⁸ The number of independent journalists, researchers, and victims’ advocates with the institutional resources to conduct such analysis can be counted on one hand. This asymmetry is not incidental to the release’s design; it is fundamental to it. The Harvard International Review documented how information overload functions within intelligence contexts: “As a person tries to complete more tasks simultaneously, his or her efficacy in dealing with each individual task diminishes in a phenomenon called ‘cognitive overload.’” The review concluded that “attempting to collect more and more information makes a nation less secure when it overloads intelligence analysts.”What degrades a nation’s security also degrades independent accountability.

'An Inside Look At Jeffrey Epstein's Demonic New York Mansion' (8 februari 2026) Een video met inleiding van en door Dimitri Lascaris.

'The criminal elite exposed in the Epstein files are burying the truth' (5 februari 2026) Een artikel van Jonathan Cook >> A

handful of figures will be sacrificed - but only to protect a wider

culture that believes rules don't apply to the ruling elite. Hier een deel van dit artikel >> The

personal attention he (Epstein) devoted to billionaires, royalty, political

leaders, statesmen, celebrities, academics and media elites was how he

kept himself at the heart of this vast network of power. His

address book was a who’s who of those who shape our sense of how the

world ought to be run. But it was also critical to how he drew some of

these same powerful figures deeper into his orbit, and into a world of

debauched and exploitative private parties in New York and on his

Caribbean island. Apparently there are another three million

documents still being withheld. Their contents, we must presume, are

even more damning to the global elite cultivated by Epstein.

'Nederland zit tot over de oren in het Epstein-dossier: 'de mainstreammedia falen hier echt grandioos'' (5 februari 2026) Een artikel van de neoliberaal rechtse publicist de Boer (ik kon geen alternatief vinden voor dit bericht) >> Nederlandse bedrijven en elites speelden een grotere rol in het Epstein-netwerk dan doorgaans wordt aangenomen. Vooral Paul Polman en Unilver het bedrijf waar hij lang een hoofdrol speelde, komen veelvuldig terug in dit artikel, waarin uiteraard ook Davos en het WEF terugkome, ook Bilderberg (de conferenties) ontbreekt natuurlijk niet. Het gaat hier om contacten na 2008, het jaar dat Epstein werd veroordeeld wegens pedofilie....

'Hundreds of ICE agents leaving Minnesota; Epstein pitched himself to MBS; Iran talks set for Friday' (5 februari 2026) Een artikel van Drop Site Daily.

'Hedonism’s Dance' (2 februari 2026) Een artikel van Binoy Kampmark, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds. >> How the Governing Classes Fell for Jeffrey Epstein.

'Vrijgegeven Epstein-bestanden werpen schokkend licht op Oekraïne, Rothschilds en internationale netwerken' (2 februari 2026) Helaas van de rechtse publicist de Boer, kon geen alternatief vinden en de informatie is te belangrijk om niet over te nemen. Hier een passage uit dit artikel >> De vrijgegeven documenten uit het Epstein-archief wijzen op zakelijke en politieke interesse van Jeffrey Epstein in Oekraïne, zowel vóór als na de coup in 2014. De stukken tonen contacten met leden van de familie Rothschild en vermelden bezoeken aan Kiev in de periode rond de verkiezing van president Zelensky. (>> junatleider Zelensky, daar ook destijds vakbonden en een aantal waaronder de grootste oppositiepartijen werden verboden voor de verkiezingen.

'"Leadership Would Like Your Help"': Indian Billionaire Tapped Jeffrey Epstein Before Modi's Visits to U.S. and Israel' (1 februari 2026) Een artikel van Meghnad Bose, Fatima Khan, and Biplob Kumar Das, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News >> New Department of Justice documents reveal Epstein’s direct role in fostering ties between Indian, Israeli, and U.S. elites.

'“Praise Allah, There Are Still People Like You”: Jeffrey Epstein Nurtured Israel-Emirates Ties Before Abraham Accords' (14 januari 2026) Een artikel van Murtaza Hussain and Ryan Grim, gepublicerd op Drop Site News >> Epstein leveraged his friendship with the chief of DP World to pitch Israeli logistics infrastructure and cybersecurity investments to the UAE.

'Epstein and Leviathan: How the Financier Opened Doors to Netanyahu and Ehud Barak Amid Israel's Offshore Gas Fight' (29 december 2025) Een artikel van Murtaza Hussain en Ryan Grim, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News >> Epstein advised on U.S. role in Israeli energy as Ehud Barak sought foreign partners to save gas monopoly. Onder andere met aandacht voor de enorme diefstal van aardgas behorend aan de Palestijnen in de Gazastrook, je zou zelfs kunnen stellen dat de Israëlische genocide op de Palestijnen tevens 'ten dienste staat' van deze diefstal.....

'A Thesis Confirmed Epstein, Dershowitz and the Israel Lobby' (29 december 2025) Een artikel van Binoy Kampmark, gepublicerd op Savage Minds.

'Epstein and the Clintons: As Hillary Launched Presidential Campaign, Epstein Feared Exposure' (19 december 2025) Een artikel van Ryan Grim and Murtaza Hussain >> Leaked emails show Ghislaine Maxwell traveled to a south Indian village with Bill Clinton in 2006, while Epstein lavished gifts on a senior Clinton aide—after Clinton supposedly cut ties.

'Jeffrey Epstein Pursued Swiss Rothschild Bank to Finance Israeli Cyberweapons Empire' (18 november 2025) Een artikel van Ryan Grim en Murtaza Hussain, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News >> Epstein on Ariane de Rothschild: “it was said to me, if Ehud [Barak] wants to make serious money, he will have to build a relationship with me. take time so that we can truly understand one another.”

Epstein is Taking Western Civilization Down with Him (15 september 2025) Een artikel van Karim, gepubliceerd op BettBeat Media >> The depraved appetites of those who rule us lay bare the true nature of Western (un)civilization. The War on Terror began the collapse, but Epstein will deliver the killing blow. >> The Epstein files have accomplished what no external force could: they have revealed the mechanism by which Western power actually operates. Not through democratic deliberation or moral leadership, but through systematic blackmail, sexual compromise, and the insatiable hunger for raping children that defines those who rule us. This is not governance—this is organized evil masquerading as statecraft. Dit arikel wijst vooral naar de VS, echter het is in de rest van het westen geen haar beter. Vergeet niet dat Epstein ook leiders van andere westerse landen dan de VS 'fêteerde' op seks met tot seksslaaf gemaakte kinderen, dezelfde leiders die de vuilbek vol hebben van moreel en ethisch handelen, die echter een openlijk gevoerde genocide hebben getolereerd en gesteund met wapens en handdrukken voor de fascistische daders in de Knesset.... Juist degenen die zich terecht hebben verzet tegen die genocide en dat nog doen worden door die leiders verguist, voor vuil en antisemiet uitgemaakt.... Leiders die het gore lef hebben om van de daken schreeuwen dat er een eind moet komen aan fake news en desinformatie, terwijl zij juist degenen zij die deze zaken dagelijks voeden.....

'Jeffrey Epstein: bewakers die fraudeerden weigerden een 'plea deal''

'Prince Andrew: het voorbeeld dat koningshuizen eindelijk moeten worden opgedoekt'

'Jeffrey Epstein en Ghislaine Maxwell werkten mede voor de militaire geheime dienst van Israël'

'Kindermisbruikers beschermd door overheden'

'Donald Trump - Jeffey Epstein: you've got to grab them by the pussy'

´Russiagate, 'couppoging tegen Trump' en kindermisbruik netwerk Epstein zijn gekoppeld´

'Prince Andrew ontkent kennis kindermisbruiknetwerk Epstein, maar........'

'Jeffrey Epstein waarschijnlijk op 'loonlijst' Mossad, de Israëlische geheime dienst'

'Jeffrey Epstein (exploitant kindermisbruik netwerk) 'overleden aan suïcide''

'Jeffrey Epstein, beheerder van een kindermisbruiknetwerk 'is gesuïcideerd' ofwel vermoord'

'Jeffrey Epstein: seksueel wangedrag van welgestelden veelal onder de pet gehouden'

---------------------------------------------

Voorts zie: 'The US & Israel Want To Depopulate Iran’s Capital' (8 maart 2026) Een artikel van Andrew Korybko. Hierin stelt hij dat Israël en de VS met opzet de grote oliereserve van Teheran hebben gebombardeerd en daarmee in brand hebben gestoken. Teheran dat toch al te kampen heeft met een watertekort, kreeg door de enorme rookontwikkeling te maken met een zwaar vervuilde regen die de stad verder onleefbaar heeft gemaakt. Het bombarderen van dergelijke oliereserves wordt als onethisch gezien, maar zoals we hebben gezien hebben Israël en de VS lak aan alle (internationale) ethische en morele regels, zoals ze dat ook hebben aan internationale wet- en regelgeving aangaande oorlogsvoering......

'Can Israel & the U.S. Sustain Iran's Military Power? (w/ Alastair Crooke) | The Chris Hedges Report' (7 maart 2026) Een video met transcript en inleiding van en door Chris Hedges >> The Iran War has just begun — but already, Iran’s military prowess, and America’s and Israel’s impulsive imperial hubris, is on full display. Hier een deel van de tekst >> Iran’s military power has seen the depletion of Israeli defensive interceptor missiles, the destruction of billion-dollar American radar systems and the diligent preparation of the Iranian leadership — Crooke explains these losses of the hegemonic West and their ally in Tel Aviv is what’s shaping the reality of the unfolding war. “The Iranians say they also have newer missiles, which they will show and unfold at a later stage. They haven’t reached that stage yet, but that is waiting to be used and deployed at the right moment. They’re quite comfortable that they have huge missile stocks that they can continue for a long war,” Crooke tells Hedges.

'Israel’s Greatest Weapon Was Fear' (8 maart 2026) Een artikel van Ramzy Baroud, gepubliceerdop Savage Minds >> And It Is Now Failing. Hier een deel van de tekst >> Yet the most profound blow to Israel’s psychological doctrine occurred decades later with the events surrounding October 7 and the war that followed. Israel’s response to October 7 was the devastating Gaza genocide. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were killed or wounded, and nearly the entire Strip was destroyed. The scale of violence was unprecedented even by the standards of previous Israeli wars on Gaza. Yet the objective was not merely military retaliation or collective punishment. It was also an attempt to restore the psychological balance that Israel believed had been shattered. This logic had been expressed years earlier by Israeli leaders. During Israel’s earlier war on Gaza in 2008–09, then-Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni openly suggested that Israel must respond in a way that demonstrates overwhelming force: When Israel is attacked, “it responds by going wild – and this is a good thing”. In other words, war itself functioned as psychological theatre. But the Gaza genocide produced a very different outcome.

'The Axis of Epstein Has Opened the Gates of Hell' (8 maart 2026) Een artikel van BettBeat Media >> Killing Schoolgirls. Destroying Water Plants. Bombing Neighborhoods. The Iran War Proves the Gaza Method Is Now the Template for World War. (en niet te vergeten het opzettelijk vernietigen van ziekenhuizen en medische posten.....)

'Iran Propaganda, Cognitive Warfare, and Media Manipulation | Pieter Rambags' (8 maart 2026) Een video van en met inleiding door Thomas Karat, hier een passage uit de inleiding >> In this interview I speak with the Dutch data analyst and peace activist Pieter Rambags who has spent years examining the intersection of data systems, propaganda, political messaging, and modern warfare. His background is not in journalism or politics, but in something far more revealing: the world of information systems and behavioral influence—the machinery behind how narratives travel, how perceptions are shaped, and how entire societies can be nudged in one direction or another.

'The War for Greater Israel' (7 maart 2026) Een artikel van Craig Murray, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Bombing Iran, Imperialism, Martyrdom and the End of the Rules-Based Order. Hier een deel van de tekst >> We are facing not only a period of unapologetic imperialism to which virtually all Western countries are prepared to defer, but a return of medievalism, both in the sheer barbarity and scale of physical abuse, as witnessed in Gaza and in general Israeli brutality, and in use of kidnap and murder as methods of high policy. Legitimising the killing and kidnap of leaders of opposing states is of course a double-edged sword. Having sanctioned genocide, mass killings and deliberate destruction of medical facilities and staff, the mass murder of children, as well as the kidnapping and murder of Heads of State, it is hard now to imagine almost any atrocity which the Western powers are in any moral position to condemn. While Iran’s military ability to strike back is limited, the ramifications of this attack will not be. The rulers of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states have reverted to the norm of being not only reliable US and Israeli satraps, but promoters of atavistic hatred of Shia Muslims. The West is deliberately exploiting the Shia/Sunni divide, as it has for centuries; but this will now destabilise the region for decades. Iraq in particular is going to be convulsed, and so will Pakistan. In Bahrain, the Shia population has been held in check by its Sunni rulers using systematic Western-sponsored murder and torture. Using it as a base to murder the Ayatollah is going to blow back.

'Melania at the UN ' (7 maart 2026) >> The Monstrous Absurdity of a War President's Wife Pleading for Children's Safety. Een artikel van Binoy Kampmark, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds, waarin hij vertelt over het gore lef dat de volidiote vrouw van de psychopathische oorlogsmisdadiger, mede-genocidepleger, pedofiel, chanteur en belastingontduiker Trump aan de dag legde met een toespraak tot de VN waarin ze sprak over vrede en de veiligheid van kinderen, terwijl haar man met het grootste gemak massa's volwassenen en kinderen vermoordt en zelfs het verhongeren van kinderen en volwassenen actief steunt en (ook mede-) verantwoordelijk is voor de vernietiging van ziekenhuizen en medische centra (zoals nu weer in Iran). Deze toespraak is voldoende om haar, als haar inhumaan walgelijke eega, internationaal strafrechtelijk te vervolgen!!

'This Is Netanyahu’s War, Stupid' (7 maart 2026) Een artikel van M.K. Bhadrakumar, de gepubliceerd op Savage Minds, waarin deze de Indiase premier Modi de maat neemt over dien meer dan achterlijke beslissing vriendschappelijke banden aan te gaan met de fascistisch, genocidale apartheidsstaat Israël (al is Modi zelf ook een fascist gezien zijn belachelijke racisme) >> How Modi's Pro-Israel Tilt Is Costing India Its Strategic Autonomy.

'Medical Networks Condemn Attacks on Iran' (6 maart 2026) Een artikel van Ana Vračar, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> US-Israeli War Threatens Civilian Health an Nuclear Safety. Zoals de genicidaal psychopathisch fascistische apartheidsstaat Israël heeft gedaan in de Gazastrook >> de vernietiging van de gezondheidszorg , zo hebben de VS en Israël ook nu weer aanvallen uitgevoerd op ziekenhuizen en medische centra..... Bovendien waarschuwen interantionale en nationale Iraanse gezondheidsorganisaties voor de aanvallen op kerncentrales vanwege het enorme gevaar van nucleaire besmetting van steden en gebieden in Iran en het enorme gevaar voor de volksgezondheid die dit met zich meebrengt......

'Israel planned this war on Iran for 40 years. Everything else is a smoke screen' (6 maart 2026) Een artikel van Jonathan Cook >> The embers of resistance – in Gaza, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen - have not been snuffed out. With the attack on Iran, they are being fanned into a fire. Waar ik aan toe zou willen voegen dat het de bedoeling is van Israel en de VS om Iran te Balkaniseren, ofwel op te delen zodat het nooit weer een macht van betekenis kan worden. Uiteraard weet men dat het een enorme leugen is dat Iran op het punt stond een kernwapen te hebben ontwikkeld, zoals deze leugen al 40 jaar wordt herhaald. Wel zal deze illegale oorlog leiden tot de wil van Iran om dan 'in godsnaam' maar een kernwapen te ontwikkelen, als dat de enige manier is om de agressie ven Israel en de VS te kenteren......

'U.S.-Israeli bombardment of Iran enters 7th day; Hundreds of thousands displaced in Lebanon amid Israeli assault; Trump fires Noem' (6 maart 2026) Een artikel van Drop Site Daily.

'Loony Bin Rationales' (6 maart 2026) Een artikel van Binoy Kampmark, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> The Continuing War on Iran. Hier de eerste passage iot dit artikel >> Villainous lunacy is abundant these days as the bombing of Iran by Israel and the United States continues. The rationale for this illegal pre-emptive war that not only lacks legitimacy but should land its perpetrators in the docks of the International Criminal Court, continues to get increasingly muddled. With US President Donald Trump now given to holding press conferences on the conflict, loony bin mutterings are becoming increasingly the norm.

'This Is Even Dumber And Crazier Than The Iraq War' (8 maart 2026) Een artikel van Caitlin Johnstone >> This is the new George W Bush. Trump is what Bush metamorphoses into when it emerges from its red cocoon. The crazier the US empire gets, the more insane its managers are becoming.Hier n og een passage uit dit artikel >> This time they’re not even pretending to care about the will of the American people. They’re not even pretending to care about humanitarian interests or the future of the people they are bombing. They’re just spouting extremely obvious lies that get fact-checked and debunked by the mainstream media in real time, and then murdering people and bragging about it.

'When the Mask Slips: What Rubio's Confession Means For You' (6 maart 2026) Een artikel van Thomas Karat. Hier een deel van dit artikel >> This war has now had — by Senator Mark Warner’s count — four or five different official justifications. Iran’s nuclear program. Their missiles. Their proxies. Regime change. A failed negotiation. Each one implies a completely different war, a different definition of victory, a different exit. You are not being given a coherent strategy. You are being given a rotating menu of reasons and asked to pick the one that makes you feel okay about it. That’s not leadership. That’s narrative management. And the only reason it works is because most people don’t have the tools to track how the story keeps shifting.

'In Iran, Israel’s morbid military cult now has the US fully in its grip' (5 maart 2026) Een artikel van Jonathan Cook >> In this catastrophic war of choice, it is Tehran fighting a rearguard action to restore geopolitical sanity. If Iran loses, god only knows where Israel and the US will drag the world next. Hier een deel van de tekst >> Rubio stated: “The president made the very wise decision: We knew that there was going to be an Israeli action, we knew that that would precipitate an attack against American forces, and we knew that if we didn’t preemptively go after them before they launched those attacks, we would suffer higher casualties.” In international law, aggression is an illegal application of force – the “supreme international crime”, according to the 1950 principles set out by the Nuremberg war crimes tribunal. But there is a potential mitigating factor if the attacking state can show it was acting pre-emptively: that is, it was acting to prevent a plausible, immediate and severe threat of attack. Rubio, however, was not suggesting that the US acted “preemptively” against a threat from Iran. He meant Washington had acted preemptively to stop its ally, Israel, from setting off a chain of military events that would lead to US soldiers being harmed. Had the Trump administration really been acting preemptively in these circumstances, the US should have attacked Israel, not Iran.

'U.S. Troops Were Told Iran War Is for “Armageddon,” Return of Jesus' (3 maart 2026) Een artikel van Jonathan Larsen, gepubliceerd op Substack >> Advocacy group reports commanders giving similar messages at more than 30 installations in every branch of the military. Niet alleen de oorlogsmisdadige volidioot Hegseth maar meerdere militaire leiders van het VS-terreurleger gebruiken de meer dan achterlijke christelijke 'Armageddon' sprookjes als onderdeel van de illegale oorlog tegen Iran waarbij dat leger alle internationale regels voor oorlogsvoering aan de laars heeft gelapt. Al is het heel goed mogelijk dat topidioten in de VS een kernoorlog zouden willen beginnen om de 'terugkomst van Jezus' te forceren..... Hier een deel van de tekst >> A combat-unit commander told non-commissioned officers at a briefing Monday that the Iran war is part of God’s plan and that Pres. Donald Trump was “anointed by Jesus to light the signal fire in Iran to cause Armageddon and mark his return to Earth,” according to a complaint by a non-commissioned officer. From Saturday morning through Monday night, more than 110 similar complaints about commanders in every branch of the military had been logged by the Military Religious Freedom Foundation (MRFF). The complaints came from more than 40 different units spread across at least 30 military installations, the MRFF told me Monday night. The MRFF is keeping the complainants anonymous to prevent retribution by the Defense Department. The Pentagon did not immediately respond to my request for comment.

'Pedro Sánchez’s Spain, the Honor of Europe' (5 maart 2026) Een artikel van Pr. Salim Lamrani, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Sánchez Says He Will Work for Peace and International Law. Respect voor deze geweldige politicus, die als enige leider van alle EU-listaten de Israëlische genocide op de Palestijnen veroordeelde en nog veroordeelt!!

''Trump’s Orwellian Board of Peace Consists Entirely of Human Rights Abusers' (5 maart 2026) Een artikel van Nick Turse, gepubliceerd op The Intercept >> An Intercept analysis finds that every single Board of Peace member state has been rebuked for human rights violations. En vergeet bijvoorbeeld niet de concentratiekampen in de VS waar ICE mensen opsluit, zelfs mensen die behoren tot de oorspronkelijke bevolking van de VS.... Verder houdt de VS, met de grootste gevangenispopulatie ter wereld, 120.000 mensen in isolatie, velen van hen meer dan 10 jaar. Deze manier van gevangenhouden is een zeer ernstige misdaad tegen de menselijkheid, een manier van martelen, die mensen geestelijk en lichamelijk kapotmaakt, niet voor niets dat men spreekt van isolatiefolter..... Kortom de VS behoort tot de meest ernstige mensenrechtenschenders ter wereld!!! Om nog maar te zwijgen over alle illegale oorlogen die de VS deze eeuw is begonnen, terwijl de unilaterale (illegale) sancties die de VS (meestal met steun van haar slaafse westerse partners, waaronder Nederland) een groot aantal landen heeft opgelegd, deze sancties zijn niets anders dan een vorm van smerige oorlogsvoering, die honderdduizenden mensen het leven hebben gekost.....

'Iraanse weerstand tegen de zoveelste georganiseerde opstand met dank aan de VS en Israël' (14 januari 2026)

'The Third Gulf War Will Greatly Expand If Trump Plays The Kurdish Card' (5 maart 2026) Een artikel van Andrew Korybko. Hier 2 passages uit dit artikel >> If Turkiye launches a military intervention in Iran along the lines of its earlier ones in Iraq and Syria to stop what it considers to be Kurdish terrorists, then its Azerbaijani ally might make a move on what it considers to be “South Azerbaijan”, and then the Gulf Arabs and Pakistan might be emboldened to join the fray too. CNN reported that “CIA working to arm Kurdish forces to spark uprising in Iran, sources say”, which will be facilitated by neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan. According to one of their sources, “the idea would be for Kurdish armed forces to take on the Iranian security forces and pin them down to make it easier for unarmed Iranians in the major cities to turn out without getting massacred again as they were during unrest in January.” The Third Gulf War will greatly expand, however, if Trump plays the Kurdish card.

'The Media’s Capitulation to Power (w/ Ahmed Eldin) | The Chris Hedges Report' (5 maart 2026) Een video met inleiding en transcript van en door Chris Hedges >> Chris Hedges and Ahmed Eldin discuss the propagandistic purpose the corporate media serves in the age of the American-Israeli project of genocidal colonialism. De reguliere westerse media zijn in handen van een paar spuugrijke figuren en brengen in feite allang eenzijdige berichtgeving over belangrijke politieke en geopolitieke zaken, daarbij lobbyen ze voor de NAVO, Israël en voor de wapenmaffia.....

'Mass Expulsion in Lebanon as Israel Expands War: “We Don’t Know Where to Go”' (4 maart 2025) Een artikel van Lylla Younes, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News >> Israel issued a sweeping displacement order for the entire region south of Litani River as it escalated its bombing campaign across Lebanon. Vergeet hierbij niet de wens van het fascistische apartheidsbewind van Israël om een groot-Israël te creëren, ofwel de illegale bezetting van Libanees grondgebied zal blijvend zijn......

'Who Decides What Is Legitimate?' (4 maart 2026) Een artikel van Ramzy Baroud, gepublicerd op Savage Minds >> Power, Democracy, and the War on Iran. Hier en deel uit dit artikel >> Benjamin Netanyahu, despite facing international legal action and accusations related to the Gaza genocide, continues to present Israel’s democratic framework as evidence of moral standing. Elections are cited as proof of legitimacy. Parliamentary debate is offered as evidence of healthy political balance. But democracy does not nullify military occupation. It does not legalize collective punishment. It does not absolve grave violations of international humanitarian law. And it does not make genocide permissible. Since World War II, democracy has often been mobilized rhetorically to justify regime change, invasions, and “preventive wars.” Iraq was invaded in the name of liberation. Afghanistan was occupied under the banner of freedom. Interventions across Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East were routinely framed as efforts to defend democratic values.

'From Gaza to Iran' (4 maart 2026) Een artikel van Robin Andersen, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Francesca Albanese and the Unmasking of a Neo-Colonial World Order. Hier een deel van de tekst >> When the Israeli lobbying group UN Watch spread disinformation about Francesca Albanese, they were trying to silence her condemnations of the true “common enemy of humanity”—the illegal system of oppressive, corporate-media-military and surveillance forces shaping a brutal new world order, and now bombing Iran. Albanese has proven to be the most important global voice defending Palestinians against the Israeli extermination campaign in Gaza that has continued for 28 months. In doing so, she exposed a growing web of neo-colonial forces at the forefront of genocide, still intent on completing the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians and turning Gaza into a multibillion-dollar resort for the billionaire class (revealed on a disgusting though rarely cited videotape). Trump’s profit-making enterprise called the “Board of Peace” convened for the first time in January, and some 60 countries were invited to join for a one-billion-dollar fee in a pay-to-play scheme that Pope Leo XIV referred to as an attempt to replace the UN. Jeremy Scahill explained on Democracy Now! what exactly this muddle of corporate shills, Netanyahu, and a group of rag-tag government representatives are dreaming up for their Epstein-Class playground on the Mediterranean. Depriving Gazans of any independent representation or defense, their terms are these; “you either fully bend the knee and accept a colonial apartheid regime [and] accept a new reality as dystopian plantation workers on Jared Kushner’s real estate project or we’re going to kill you.” As Asal Raad pointed out, “’They’re building resorts on the graves of Palestinians…slaughtered in a genocide—for profit—and @nytimes calls it a ‘glittering plan.’”

'EXCLUSIVE: Iran’s Deputy Foreign Minister Rejects Trump’s “Big Lie” About Why He Went to War' (4 maart 2026) Een video van en met tekst-inleiding door Jeremy Scahill >> Esmail Baghaei, a senior Iranian official, discusses the U.S. narrative, Iran’s strikes across the region, and prospects for diplomacy in a half-hour interview with Jeremy Scahill.

'When the Wells Run Dry' (3 maart 2026) Een artikel van Elhabib Benamara, gep0ubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Iran’s Water Collapse and Regional Lessons. Hier een passage uit dit artikel waaruit blijkt waar de westerse terreursancties toe kunnen leiden >> It would be incomplete to attribute this catastrophe solely to internal mismanagement without naming those who, from the outside, have deliberately asphyxiated the Iranian people. The United States, through a sanctions regime among the harshest ever imposed on a country, bears an overwhelming responsibility in this water tragedy. These sanctions have methodically hindered access to modern water management technologies, including advanced irrigation, desalination, and recycling systems that countries like the occupying power have been able to develop freely. They have prevented the import of spare parts for aging infrastructure, condemning treatment plants and distribution networks to accelerated degradation. They have isolated Iranian engineers and hydrologists from international scientific cooperation that could have been beneficial. They have blocked access to international financing that would have allowed massive investments in resource preservation. They have turned every modernization attempt into an obstacle course, discouraging initiatives and paralyzing public action.

'Death toll in Iran tops 1,000; Trump weighs arming Kurdish forces to attack Iran; Israel orders mass displacement of all of southern Lebanon' (4 maart 2026) Een artikel van Drop Site Daily. Hier een passage van de tekst >> U.S. and Israeli airstrikes pound Iran for a fifth day, killing civilians: The U.S.-Israeli war on Iran has entered its fifth day with new waves of intense bombing targeting Tehran and other areas. U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) said it has struck nearly 2,000 targets since Saturday. In the past 24 hours, the IRGC has recorded 104 attacks across 19 of the country’s provinces, with strikes hitting military bases, medical centers, and residential areas. A statement from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps detailed several incidents from yesterday’s strikes. A U.S. Tomahawk missile struck a residential home in Oshnavieh County, killing an entire family; an air-launched missile hit a private car in Salman County, killing five; and a missile strike in the Qasemiyeh neighborhood of Urmia killed an elderly couple. The statement also reported strikes on residential homes and a wedding hall in Kangavar County. The IRGC warned that “none of these crimes and innocent massacres will go unanswered.” Casualty counts: The death toll in Iran has reached 1,045 people, according to the official Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs, state media reported. The foundation said the death toll represented the number of bodies that have been identified and prepared for burial. Meer dan 1.045 doden en nog zijn er mensen, waaronder gevluchte Iraniërs, die zo grof inhumaan zijn om te pleiten voor het doorgaan van de VS-Israëlische terreur middels bombardementen.....

'Spain’s Defiance in a World of Coercion' (4 maart 2026) Een artikel van Kurniawan Arif Maspul, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Madrid’s Moment of Defiance and the Unravelling of Unipolar Assumptions. Hier een passage uit de tekst >> In a season of raw power politics, a single act of refusal can sound like thunder. When Washington reportedly threatened to ‘cut off all trade’ with Spain after Madrid declined to allow US bases on its soil to be used for strikes on Iran, the expectation was compliance. Instead, Spain invoked international law and European Union treaties, calmly insisting that any change in relations must respect legal obligations and multilateral agreements. In an era where middle powers are often assumed to bow before superpower fury, Spain chose a different script. De psychopathische topidioot Trump dreigde Spanje hoge tarieven op te leggen, helaas voor deze pedo, oorlogsmisdadiger en mede-genocidepleger exporteert Spanje slecht 4% van haar totale export naar de VS, deze vereniging van terreurstaten exporteert veel meer naar Spanje.... ha! ha! ha! ha!

'Africa Responds to the War on Iran ' (4 maart 2026) Een artikel van Pavan Kulkarni, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Mixed Messaging From African Leaders on Us-Israel War on Iran. Hier de conclusie aan het eind van de tekst, waarin wordt uitgelegd dat de meeste Afrikaanse leiders de schuld bij Iran leggen, dan wel zich op de vlakte houden >> “This is not a conflict about nuclear weapons or regional stability, as the propaganda machines of the West would have us believe. It is a conflict about control, resources, and the suppression of any nation that dares to chart an independent path free from the dictates of Washington and London.”

'Debunked and Confirmed' (3 maart 2026) Een artikel van Ramzy Baroud, gepubliceerd opSavage Minds >> Myths and Realities from the Iran War. Hier een deel van de tekst >> For decades, Washington has portrayed itself as the ultimate guarantor of regional security. US military bases, aircraft carriers, air defense systems and bilateral security agreements were marketed as shields protecting allies from existential threats. This war has exposed that promise as hollow. Despite overwhelming US military presence across the Gulf, regional allies have faced missile alerts, drone incursions and maritime threats. American troops themselves have been killed. Energy infrastructure has been threatened. Shipping routes have been destabilized. The presence of American forces has not prevented escalation; it has invited it. More importantly, the nature of US presence has been exposed. It is not rooted in partnership but in dominance. Yet even dominance has proven illusory. Military superiority does not automatically translate into strategic control. When a regional power like Iran chooses to retaliate asymmetrically, the illusion of total American command evaporates.

'This Illegal US-Israeli Attack on Iran Is Also an Assault on the United Nations' (3 maart 2026, een artikel van Jeffrey Sachs en Sybil Fares, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> How the US-Israeli Attack on Iran Killed the International Rule of Law. Hier de erste 3 passages van dit artikel >> On 16 February 2026, one of us (Jeffrey Sachs) sent a letter to the UN Security Council warning that the United States was on the verge of tearing up the United Nations Charter. That warning has now come to pass. The United States and Israel have launched an unprovoked war against Iran in flagrant violation of Article 2(4) of the Charter, without authorization from the Security Council, and without any legitimate claim of self-defense under Article 51. They are trying to kill the UN Charter and the international rule of law, but they will fail. At the Security Council on 28 February 2026, the US and its allies directed their condemnation not at the American and Israeli aggression, but at Iran. One US ally after the next condemned Iran for its retaliatory attacks yet absurdly failed to condemn the illegal and unprovoked US-Israeli attack on Iran. This performance by these countries was disgraceful and turned reality completely upside down. The joint US-Israeli attacks were described by Trump as necessary because Iran “rejected every opportunity to renounce their nuclear ambitions, and we can’t take it anymore.” This is of course a flat lie. As the letter of 16 February recounted, Iran agreed a decade ago to a nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) that was adopted by the UN Security Council in Resolution 2231. It was Trump who ripped up the agreement in 2018. In June 2025, Israel bombed Iran in the midst of US-Iran negotiations. This time too, the Israel-US war plans were set weeks ago when Netanyahu met with Trump, and the negotiations underway between the US and Iran were a charade. This seems to be the new modus operandi of the US: start negotiations and then aim to murder the counterparts.

'Going Native in the Trump Jungle ' (3 maart 2026) Een artikel van Binoy Kampmark >> How it became Legal to Attack Iran. Hier een deel van de tekst >> The United Kingdom has gone one better by becoming entirely revisionist. In a 1 March statement, the government of Sir Keir Starmer revealed why the UK would be committing to the conflict against Tehran. This was not about Iran being pre-emptively and unlawfully attacked in the first place but Iran daring to defend itself by attacking regional powers hosting US military bases and personnel. Britain would therefore be mounting, at the insistence of Washington, a “defensive action” by targeting “missile facilities in Iran which were involved in launching strikes on regional allies.” It would also act “in the collective self-defence of regional allies who have requested support.” Any propaganda minister in the annals of history would have been proud of that fatuous formulation.

(ha! ha! ha! Deze gigantische hypocriet en houten Klaas is premier van Groot-Brittannie!!) British Prime Minister Starmer said Sunday he had agreed to let the

United States use UK bases to fire “defensive” strikes aimed at

destroying Iranian missiles and their launchers. Photo credit: Jonathan

Brady

'Too Depraved to Defect: Why the Gulf Kingdoms Would Rather Bend Over Than Jump Ship' (3 maart 2026) Een artikel gepubliceerd op BettBeat Media, een analyse die aangeeft dat een stel walgelijk stinkende pedofielen en slavenhouders de welgestelden en machthebbers zijn in de Golfstaten (en reken maar dat westerse welgestelden en politici graag op bezoek gaan bij dat geteisem) >> The Gulf monarchies would rather take it up their asses, repeatedly, by their allies than be liberated by Iran. Because liberation, for them, means the end of depravity and opulence.

'The casino-fication of war' (3 maart 2026) Een artikel van Judd Legum, Rebecca Crosby en Noel Sims. Gokken op oorlogsvoering, een nieuwe zeer zieke en misdadige vorm van oorlogswinstmaken.....

'If Westerners Could Wrap Their Minds Around What War Really Is' (3 maart 2026) Een artikel van Caitlin Johnstone >> War is the worst thing in the world. Westerners talk about it like it’s a fucking video game, like “hurr durr, we just go in there and achieve our objectives and win,” when really war means shredding human bodies to bits.

'Roguish Justifications' (2 maart 2026) Een artikel van Binoy Kampmark, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds. >> The Apologists for the Attack on Iran. Binoy geeft hier commentaar op de smerige en laffe reacties van westerse leiders, waar allleen de Spaanse premier Pedro Sánchez de gunstige uitzondering was. Hier een deel van de tekst >> Canberra simply “recognised that Iran’s nuclear program is a threat to global peace and security. The international community has been clear that the Iranian regime can never be allowed to develop a nuclear weapon.” Disingenuously, the statement referred to the reimposition of UN Security Council sanctions on Tehran for not complying with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action without mentioning that Trump, with Israeli pressure, sabotaged it in the first place. “We support the United States acting to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon and to prevent Iran continuing to threaten international peace and security.” If ever a servile poltroon could be expected to write a note of approval for the savaging of international law and the undermining of the UN order, this was it. The Canadian government of Mark Carney took much the same line. “Canada,” stated Prime Minister Carney and Foreign Affairs Minister Anita Anand, “supports the United States acting to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon, and to prevent its regime from further threatening international peace and security.” This endorsement of unlawful aggression prompted Lloyd Axworthy, a previous foreign affairs minister, to call it “an abandonment of a long-standing element of our foreign policy.” Former Canadian diplomat Sabine Nölke also noted that there was no “logical connection to why we are now supporting a prima facie illegal act of war of aggression.” There was no necessity in attacking Iran; this was but a “war of choice.” France, Germany and the United Kingdom, in a joint statement, reiterated the scolding line of Iran as the all central threat, be it with its nuclear and ballistic missile program, its subversive activities, and its human rights abuses. The only strikes to be condemned were not the pre-emptive ones of Israel and the United States, in which the three countries played no part, but Iran’s “indiscriminate military strikes.” The European Union was also mealy mouthed, never condemning the US-Israeli actions as a breach of international law in its 1 March statement, focusing instead on its meritorious sanctions policy on Iran, Tehran’s bleak human rights record, and “Iran’s ballistic missile and nuclear programmes, and its support for armed groups in the Middle East.” The EU had consistently urged Iran to end its “nuclear programme, curb its ballistic missile programme, refrain from destabilizing activities in the region and in Europe, and to cease the appalling violence and repression against its own people.” The European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, instead of condemning the attacks as having the potential to sunder regional security, demanded a “credible transition in Iran”. Kaja Kallas, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, seemed to celebrate the killing of Ali Khamenei as “a defining moment in Iran’s history.” While uncertainty had presented itself, there was “now an open path to a different Iran, one that its people may have greater freedom to shape.” Both officials are clearly untutored on the disasters of imposed change upon Iran and other countries in the Middle East, where the people’s wishes are inconsequential to foreign meddlers.

'US Calls Iranian Retaliatory Strikes "Unprovoked", And Other Notes' (2 maart 2026) Een artikel van Caitlin Johnstone. Hier een passage uit de tekst >> At least 153 people were reportedly killed in a strike on an Iranian girls’ school in the opening wave of attacks. Most of the fatalities were girls between the ages of seven and twelve. Turns out “freeing Iranian women from the hijab” just meant killing girls before they’re old enough to start wearing one. There’ve been viral claims on social media that it was a misfired Iranian missile which struck the school and that the Iranian government has admitted to this — both of which were swiftly debunked. We’ve seen this play before. In October 2023 hasbarists were saturating the information ecosystem with claims that Gaza’s Al-Ahli Baptist hospital was hit by a misfired Palestinian rocket rather than by Israel. Israel has now bombed that very same hospital eight separate times, which tells you all you need to know.

'Witnesses Describe Horror Scene After “Double-Tap” Bombing Kills Over 20 at Popular Tehran Square' (2 maart 2026) Een artikel van Reza Sayah en Murtaza Hussain, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News >> In Iran, the U.S. and Israel are employing tactics used in Israel’s genocide in Gaza, the “War on Terror” and Trump’s recent attacks on alleged drug boats in the Carribean. Kortom een uiterst laffe aanval, die als misdaad tegen de menselijkheid moet worden gezien.....

'Minab’s Children and the Shattering of Restraint' (2 maart 2026) Een artikel van Kurniawan Arif Maspul, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> How a School Bombing in Iran Shook the World, and Why It Matters Now.

'The Nihilism of Trump’s War Games' (gepubliceerd op Truthdig: 3 maart 2026) Een column met tevens een vooruitziende blik van Jeb Lund van 27 februari 2026. At home and abroad, demonstrating strength through punishment is more important than “victory.”

'Trump’s Iran Attack Was Illegal, Former U.S. Military Officials Allege' (2 maart 2026) Een artikel van Austin Campbell, gepublicerd op The Intercept >> “This is an introduction of U.S. forces into hostilities. It absolutely triggers the 48-hour notice requirement.”

'After a Sports Hall in Iran Was Bombed, Witnesses Describe Chaos and “Continuous Screaming” ' (1 maart 2026) Een artikel van Mahmoud Aslan, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Several hours after a bomb struck a girls’ elementary school and killed 165, a strike on the town of Lamerd killed teenagers in a gymnasium. Hier een passage uit dit artikel >> The bombing of the sports hall in Lamerd came hours after a strike on a girls’ elementary school in Minab, another small city on the Persian Gulf, further east near the Strait of Hormuz, that, according to the state-run IRNA news agency, killed 165 people, many of them schoolgirls. Neither the U.S. nor Israel claimed that strike. The Israeli military said it was not aware of strikes in the area of Minab; CENTCOM’s spokesperson said they were “looking into” reports. Another strike hit an adjacent IRGC naval base and the USS Abraham Lincoln is stationed nearby. Bij deze laffe aanval werden 18 Iraniërs vermoord, terwijl een flink aantal mensen (ook zwaar) gewond raakten...... In totaal zouden er nu (3 maart 2026 om 12.00 u. 800 doden zijn te betreuren, ofwel Iraniers die zijn vermoord.....

'Iran Prepared for an Existential War. How Much Are Trump and Israel Willing to Gamble?' (1 maart 2026) Een artikel van Jeremy Scahill en Murtaza Hussain, gepubliceerd op Drop Site News >> Iran is intensifying strikes across the region after Supreme Leader Khamenei's assassination, as Trump floats new talks and more bombing. Hier een deel van de tekst >> The New York Times followed with a breathless account published Sunday purporting to tell the secret story of how the CIA and Israel hunted down Khamenei, “tracking him for months” and “gaining more confidence about his locations and his patterns,” before pinpointing his location so he could be killed. “People briefed on the operation described it as a product of good intelligence and months of preparations,” the report claimed. Khamenei’s secret location, it turned out, was simply his office.

'Regime Change, the Double-Edged Sword' (1 maart 2026) >> "Epic Fury" was initiated with the end of the Iranian regime in mind. Regime change may indeed be the result of this attack. But the question of who will be gone when the dust settles is not clear. Een artikel van Scott Ritter, waarin hij o.a. het sjiitische geloof uitlegt en stelt dat het vermoorden van de sjiitische leider Khamenei te vertgelijke is met het vermoorden van de paus, de aartsbisschop van Canterbury (het hoofd van de Anglicaande kerk), of het hoofd van de Russisch-orthodoxe kerk, wat bij de gelovigen van deze religies enorme woede zal opwekken. Khamenei zelf wilde sterven als martelaar en dat heeft Israël voor elkaar gekregen.... Terecht stelt Ritter dan ook dat de Iraniërs i.p.v. "Dood aan Khamenei" te roepen, nu roepen: "Lang leven de martelaar Khamenei"

People demonstrate in support of Ali Khamenei

'“Small Children Who Knew Nothing of Politics or Wars”' (28 februari 2026) Een artikel van Drop Site News >> A scene of devastation in Minab, Iran, as parents waited to know the fate of their young daughters after the bombing of a girls' elementary school killed over 100. Op 1 maart meldde de BBC dat het om meer dan 140 slachtoffers ging die bij de aanval op de school omkwamen (meer dan 140 kinderen waar onder het totaal zich uiteraard ook docenten enz. (bevinden): 'At least 153 dead after reported strike on school, Iran says'

'Iran Is Being Destroyed. You're Being Managed. Here's How' (1 maart 2026) Een artikel van Thomas Karat. Hier een deel van de tekst >> By the time you read this, you’ll have already decided how you feel about the US-Israel attack on Iran. You might not have consciously chosen a position, but your brain has. It happened somewhere between the third headline and the second clip of smoke over Tehran. Fast, automatic, below awareness. This is what psychologists call the “mere exposure effect” crossed with something older and deeper — your brain’s threat-detection system doing what 300,000 years of evolution designed it to do: sort incoming signals into safe/dangerous, us/them, act/freeze. That system kept your ancestors alive on the savannah. It is absolutely useless for evaluating a joint military operation across six countries with cascading second-order effects on global energy markets. But it already ran. And now you have a feeling. And that feeling is going to do something dangerous: it’s going to masquerade as an opinion.

'A War That Cannot Be Won' (1 maart 2026) Een artikel van Vijay Prashad, gepubliceerd op Savage Minds >> Israel and the United States Bomb Iran. Vijay maakte een fout in dit artikel volgens hem werde in 1996 sancties ingesteld tegen Iran, echter de sancties tegen Iran werden in 1979 ingesteld en in 1995 verscherpt door de 'cigar-man', hoogstwaarschijnlijk pedofiel en oorlogsmisdadiger Clinton.

'One Power Can Prevent the End of Humanity. But Then It Has to Speak' (26 februari 2026) Een artikel van Karim, gepubliceerd op BettBeat Media >> As Netanyahu draws India into his “Hexagon of Alliances” and the US-Iran confrontation reaches a breaking point, the world hurtles toward catastrophe — and China watches from the sidelines.

'Going to War, Again, for Israel' (28 februari 2026) Een artikel van Chris Hedges. Hier een deel van de tekst >> Once again, America is going to war for Israel. Once again, many will die for the Zionist state, including American service members. Once again, we will stumble blindly into a military fiasco. Once again, we will do the bidding of a foreign power whose interests are not our interests, but whose lobbyists have bought up our political class, including Donald Trump. Once again, we will violate the U.N. charter by attacking a country that does not pose an imminent threat. This is not our war. This is part of Israel’s demented vision of Greater Israel, of dominating the Middle East. But Israel needs our military, our taxpayer dollars, our weapons to do it. And we have handed them the keys to our formidable arsenal. The architects of the war with Iran, which the administration feels no need to justify to the American public or the international community, admit it will not be quick.

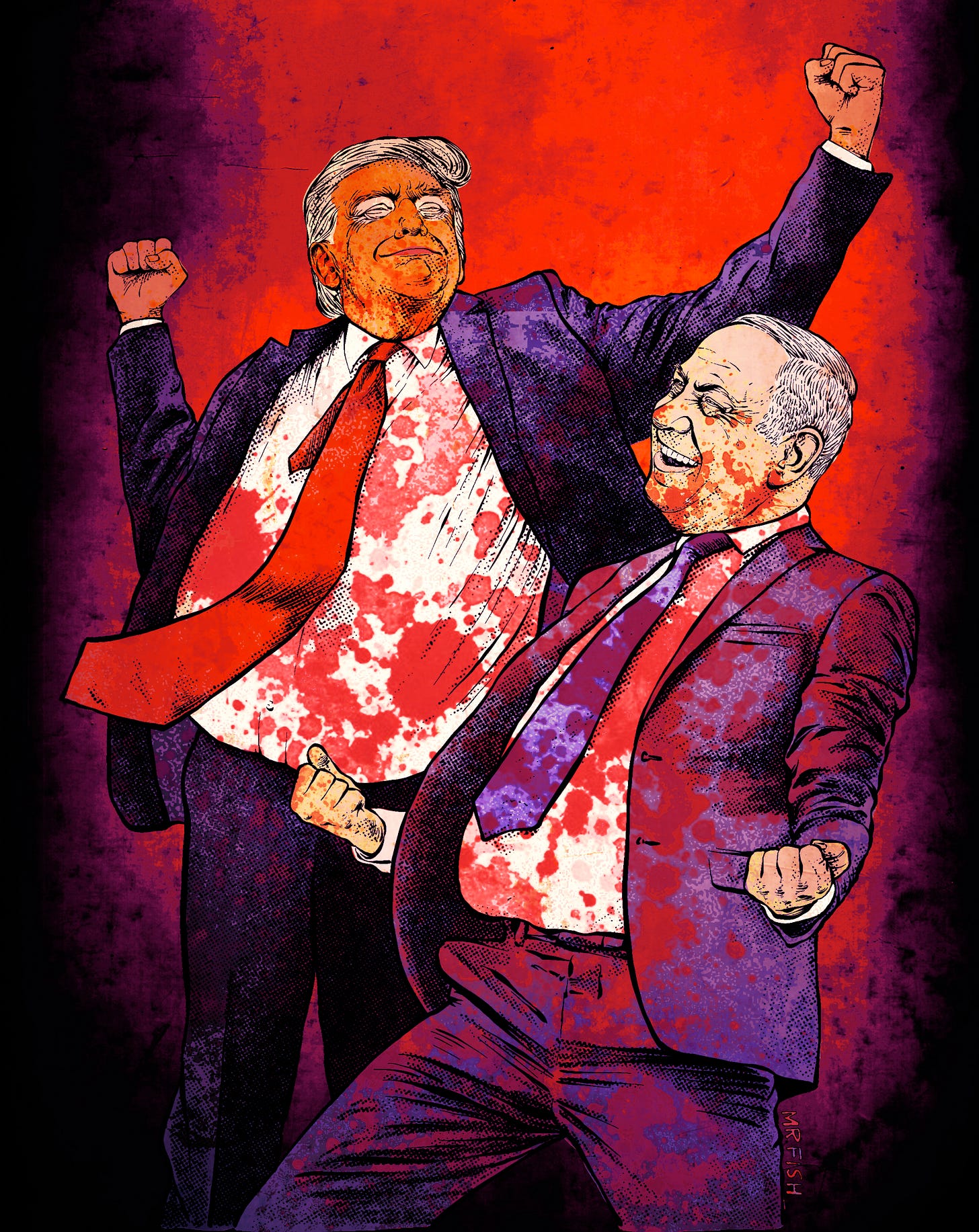

Blood Brothers by Mr. Fish