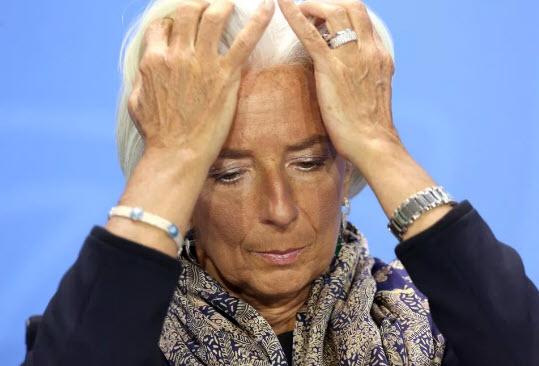

Lagarde

heeft afgelopen vrijdag de baan van topgraaier Draghi als president van de Europese Centrale Bank (ECB) overgenomen, ook al heeft zij bepaald geen financieel economische opleiding gevolgd. Alle hoop van een aantal centrale banken in de EU

op een ander beleid dan dat van Draghi werd vrijwel onmiddellijk de

grond ingeboord. Vreemd overigens die verwachting, immers Lagarde is ook verantwoordelijk voor de gore spelletjes die het IMF sinds 2011 heeft gespeeld, in dat jaar werd ze directeur van deze inhumane neoliberale organisatie.....

Overigens, Lagarde is in feite een veroordeelde misdadiger, die haar straf van een jaar gevangenisstraf ontliep daar er anders een crisis in het IMF zou zijn ontstaan, dit nadat haar voorganger en verkrachter Strrauss-Kahn het veld moest ruimen..... Ongelofelijk daarom ook dat de ondemocratische EU Lagarde koos als topgraaier van de ECB.......

Overigens, Lagarde is in feite een veroordeelde misdadiger, die haar straf van een jaar gevangenisstraf ontliep daar er anders een crisis in het IMF zou zijn ontstaan, dit nadat haar voorganger en verkrachter Strrauss-Kahn het veld moest ruimen..... Ongelofelijk daarom ook dat de ondemocratische EU Lagarde koos als topgraaier van de ECB.......

Lagarde nam haar functie bij de ECB op o.a. door Nederland en Duitsland te manen hun overschot te investeren, voorts begon Lagarde te zeuren over onderlinge 'solidariteit', ofwel steek ook je kont diep in de schulden. Wat betreft het 'beleid' van Draghi: Lagarde gaat gewoon door op de doodlopende weg die Draghi eerder heeft bewandeld: obligaties van landen opkopen en het verlagen van de rente tot nog verder onder de – 0,5%, die nu al ingevoerd wordt (zo ongeveer de laatste actie van Draghi), ofwel een rente die nog verder onder het 'nulpunt' zal dalen, anders gezegd: negatieve rente (waarmee geld lenen zelfs geld zou moeten opleveren, al zal dat 'natuurlijk niet' voor het gewone volk opgaan...)....

Dat

daardoor een flink aantal mensen in de problemen komt interesseert

autocraat Lagarde net zo min als haar voorganger Draghi, schijt aan de pensioenen die mensen hun

werkende leven lang hebben opgebouwd, dokken en niet zeuren....... Ook de kleine spaarders kunnen wat Lagarde betreft doodvallen, ze durfde keihard te zeggen

dat je beter een baan kan hebben dan geld op de bank..... Moet je

nagaan: de misdadige dweil Lagarde gaat een inkomen verdienen van rond de 4 ton op

jaarbasis is en dat is exclusief een gigantische onkostenvergoeding......

Taaie

stof mensen, het hieronder opgenomen artikel van Tyler Durden, maar zeer de moeite van het lezen waard (het artikel werd eerder gepubliceerd op Zero Hedge). Daaronder een verduidelijking over QE ofwel Quantitative Easing, een artikel

van Investopedia, QE of het waanzinnige beleid van Draghi om zoveel

mogelijk obligaties van EU landen op te kopen (ook werden schulden van banken in Zuid-Europa opgekocht, waardoor de Grieken de regie in eigen land zijn kwijtgeraakt en nog steeds diep in de ellende zitten...)....

De ECB heeft overigens al aangekondigd, na de stop van één jaar, opnieuw bonussen ter waarde van 20 miljard euro op te willen kopen, ook al is het allesbehalve duidelijk of dit ook maar iets heeft opgeleverd voor de EU, behalve dan dat de drukpersen voor papiergeld overuren maakten en ons geld in feite steeds minder waard werd ook al merken we daar nu nog weinig van..... (dat gebeurt als de volgende crisis zich aandient en zoals je weet die komt eraan, de vraag is wanneer precies)

De ECB heeft overigens al aangekondigd, na de stop van één jaar, opnieuw bonussen ter waarde van 20 miljard euro op te willen kopen, ook al is het allesbehalve duidelijk of dit ook maar iets heeft opgeleverd voor de EU, behalve dan dat de drukpersen voor papiergeld overuren maakten en ons geld in feite steeds minder waard werd ook al merken we daar nu nog weinig van..... (dat gebeurt als de volgende crisis zich aandient en zoals je weet die komt eraan, de vraag is wanneer precies)

Lagarde: "We Should Be Happier To Have A Job Than To Have Savings"

by Tyler

Durden

Mon,

11/04/2019 - 06:12

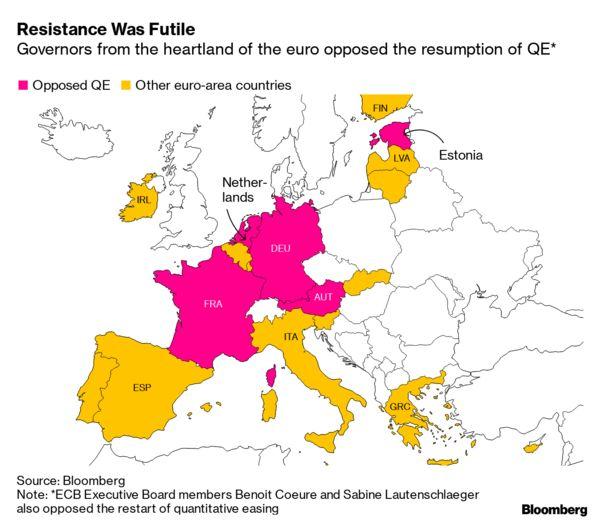

Any

hopes that the replacement of Mario Draghi, who on Halloween left the

ECB more polarized than ever, as the core European nations revolted

against the Italian's profligately loose monetary policy in an

unprecedented public demonstration

of discord within

the European Central Bank...

...

with the ECB's new head, former IMF Director and convicted

criminal,

Christine Lagarde would result in some easing of tensions, were

promptly crushed when Lagarde picked up where Draghi left

off, calling

on Germany and the Netherlands to use their budget surpluses to fund

investments that would help stimulate the economy, in

a sharp rebuke that will not win the former French finance minister

any friends in fiscally conservative Germany.

In

an appeal to Germany's sense of solidarity, and in hopes that

Germany's memory of hyperinflation has faded enough, Lagarde said

that there "isn’t enough solidarity" in the single

currency area, adding: “We share a currency, but we don’t share

much budgetary policy for now."

"Those

that have the room for manoeuvre, those that have a budget surplus,

that’s to say Germany, the Netherlands, why not use that budget

surplus and invest in infrastructure? Why not invest in education?

Why not invest in innovation, to allow for a better rebalancing?"

asked Lagarde, blaming Germany and the Netherlands for living within

their means, and demanding they should no longer do so, just

because most other Europeans decided to pull a page out of the

American playbook, and live exorbitantly outside of

their means.

Lagarde's

direct attempt at shaming Europe's fiscal conservatives was nothing

short of shocking: normally ECB officials avoid naming individual

countries in public statements, because their mandate is to act in

the interests of the eurozone as a whole. But when Lagarde made her

speech she had not yet officially taken over at the Frankfurt-based

institution — she succeeds Mario Draghi on Friday.

We

somehow doubt this "explanation" will fly with the German

population, which sees itself as funding peripheral Europe's

profligate ways for the past decade, even as it benefited from the

weak euro to supercharge the German export machine.

And

just to guarantee she is as resented by Germany as was Mario Draghi,

she said that the German and Dutch governments, which last year had

budget surpluses of 2% and 1.5% respectively, "have

not really made the necessary efforts," she

added, referring to establishment's increasing desperation to force

anyone with an even remotely normal balance sheet to sink to the same

level as their insolvent peers.

As

for the punchline, Lagarde defended the negative interest rates

introduced by her predecessor Draghi, arguing

that people should be happier to have a job than a higher savings

rate. This,

as a reminder, comes at a time when virtually everyone who

is not named

"Draghi" or "Lagarde" thinks that negative

rates are catastrophic,

and assure doom for the Eurozone.

When asked about the impact of negative rates on savers, Ms Lagarde said on Thursday that they should think about how much worse the situation would be if the ECB had not cut rates as much as it had.

“Would we not be in a situation today with much higher unemployment and a far lower growth rate, and isn’t it true that ultimately we have done the right thing to act in favor of jobs and of growth rather than the protection of savers?” she asked.

The unemployment rate in the 19-country eurozone has fallen from 12 per cent in 2013 to 8.2 per cent last year. GDP growth in the single currency zone was 1.8 per cent last year and the ECB expects it to slow to 1.1 per cent this year.

Finally,

for those curious if the authorities will stop

at anything to

destroy the currency and send rates to even more negative levels if

it means kicking the can on a global, populist uprising, by just a

few months, weeks or days, here is the answer: "We

should be happier to have a job than to have our savings

protected," said

Lagarde.

"I think that it is in this spirit that monetary policy has been decided by my predecessors and I think they made quite a beneficial choice."

Let's check back on that statement in a year, shall we?

Of

course, there is no magic solution here: all the ECB has done is kick

the can, and ensure that the next crisis will be even worse than if

some semblance of a price-clearing reality had been allowed under

Draghi's 8 years. Instead, the ECB's balance sheet exploded to €4.7

trillion euros, as the world's largest central

bank-cum-hedge fund bought every bond in sight in hopes

of keeping asset prices artificially elevated.

In October, the ECB, less than a year after it ended QE* in a failed attempt to "renormalize" monetary policy, announced it would cut rates to a record -0.5% and unveiled open-ended plans to start buying €20bn of bonds starting in November.

Needless

to say, the comments by the former French finance minister confirm

market expectations that she is likely to pursue similar monetary

policy strategy to Draghi who flooded the financial system with cheap

money to fight slowing growth and inflation while calling on

governments to do more through fiscal policy to take the burden off

the central bank.

In the end, the consequences of Draghi's monetary policy, as we explained before, will be catastrophic, but the former Goldman partner was wise enough to get off the European Titanic before it hit the iceberg. It will now be Lagarde's task to save as many people as possible once the ship starts sinking, and judging by her remarks, she is perfectly fine of not only going down with the ship, but also being blamed for the collision.

Tags: Business Finance

===============================

* Hieronder de uitleg over QE of: Quantitative Easing, geschreven door Jim Chappelow en gepubliceerd op Investopedia (zie ook het eerste staatje in het artikel van Durden):

Quantitative Easing (QE)

In the end, the consequences of Draghi's monetary policy, as we explained before, will be catastrophic, but the former Goldman partner was wise enough to get off the European Titanic before it hit the iceberg. It will now be Lagarde's task to save as many people as possible once the ship starts sinking, and judging by her remarks, she is perfectly fine of not only going down with the ship, but also being blamed for the collision.

Tags: Business Finance

===============================

* Hieronder de uitleg over QE of: Quantitative Easing, geschreven door Jim Chappelow en gepubliceerd op Investopedia (zie ook het eerste staatje in het artikel van Durden):

Quantitative Easing (QE)

What Is Quantitative Easing? (QE)

Quantitative

easing is an unconventional monetary

policy in

which a central bank purchases government

securities or

other securities from the market in order to increase the money

supply and encourage lending and investment. When short-term

interest rates are at or approaching zero, normal open

market operations,

which target interest rates, are no longer effective, so instead a

central bank can target specified amounts of assets to purchase.

Quantitative easing increases the money

supply by

purchasing assets with newly created bank reserves in order to

provide banks with more liquidity.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Quantitative easing (QE) is the name for a strategy that a central bank can use to increase the domestic money supply.

- QE is usually used when interest rates are already near 0 percent and can be focused on the purchase of government bonds from banks.

- QE programs were widely used following the 2008 financial crisis, although some central banks, like the Bank of Japan, had been using QE for several years prior to the financial crisis.

Understanding Quantitative Easing

To

execute quantitative easing, central

banks increase

the supply of money by buying government

bonds and

other securities. Increasing the supply of money is similar to

increasing supply of any other asset—it lowers the cost of money.

A lower cost of money means interest

rates are

lower and banks can lend with easier terms. This strategy is used

when interest rates approach zero, at which point central banks have

fewer tools to influence economic growth.

If quantitative easing itself loses effectiveness, fiscal policy (government spending) may be used to further expand the money supply. In effect, quantitative easing can even blur the line between monetary and fiscal policy, if the assets purchased consist of long term government bonds that are being issued to finance counter-cyclical deficit spending.

The Drawbacks of Quantitative Easing

If central banks increase the money supply, it can cause inflation. In a worst-case scenario, the central bank may cause inflation through QE without economic growth, causing a period of so-called stagflation. Although most central banks are created by their countries' government and are involved in some regulatory oversight, central banks can't force the banks to increase lending or force borrowers to seek loans and invest. If the increased money supply does not work its way through the banks and into the economy, QE may not be effective except as a tool to facilitate deficit spending (i.e. fiscal policy).

Another potentially negative consequence is that quantitative easing can devalue the domestic currency. For manufacturers, this may help stimulate growth because exported goods would be cheaper in the global market. However, a falling currency value makes imports more expensive, which can increase the cost of production and consumer price levels.

Is Quantitative Easing Effective?

During the QE programs conducted by the U.S. Federal Reserve starting in 2008, the Fed increased the money supply by $4 trillion. This means that the asset side of the Fed's balance sheet grew significantly as it purchased bonds, mortgages, and other assets. The Fed's liabilities, primarily reserves at U.S. banks, grew by the same amount. The goal was that the banks would lend and invest those reserves to stimulate growth.

However,

as you can see in the following chart, banks held onto much of that

money as excess reserves. At its peak, U.S. banks held $2.7 trillion

in excess reserves, which was an unexpected outcome for the Fed's QE

program.

(voor de staat die hier hoort te staan, zie het origineel)

Most economists believe that the Fed's QE program helped rescue the U.S. (and world) economy following the 2008 financial crisis. However, the magnitude of its role in the subsequent recovery is more debated and impossible to quantify. Other central banks have attempted to deploy QE to fight recession and deflation with similarly cloudy results.

Following

the Asian

Financial Crisis of 1997,

Japan fell into an economic recession.

Beginning in 2000, the Bank

of Japan (BoJ) began

an aggressive QE program to curb deflation and to stimulate the

economy. The Bank of Japan moved from buying Japanese government

bonds to buying private debt and stocks. The QE campaign failed to

meet its goals. Ironically, the BoJ governors had concluded that "QE

was not effective" just months before launching their program

in 2000. Between

1995 and 2007,

Japanese GDP fell from $5.45 trillion to $4.52 trillion in nominal

terms, despite the BoJ's efforts.

The Swiss

National Bank (SNB) also

employed a QE strategy following the 2008 financial crisis.

Eventually, the SNB owned assets nearly equal to annual economic

output for the entire country, which made the SNB's version of QE

the largest in the world as a ratio to GDP.

Although economic growth has been positive during the subsequent

recovery, how much the SNB's QE program contributed to that recovery

is uncertain. For example, although it was the largest QE program in

the world as a ratio to GDP and interest rates were pushed below 0%,

the SNB was still unable to achieve its inflation targets.

In

August 2016, the Bank

of England (BoE) announced

that it would launch an additional QE program to help alleviate

concerns over "Brexit."

The plan was for the BoE to buy 60

billion pounds of

government bonds and 10 billion pounds in corporate debt. If

successful, the plan should have kept interest rates from rising in

the U.K. and stimulated business investment and employment.

From August 2016 through June 2018, the Office for National Statistics in the U.K. reported that gross fixed capital formation (a measure of business investment) was growing at an average quarterly rate of 0.4 percent, which was lower than the average from 2009 through 2018. The challenge for economists is to detect whether growth would have been worse without quantitative easing.