Oktober vorig jaar liepen 4 VS militairen in een hinderlaag waarbij ze omkwamen, dit gaf nogal wat ophef in de VS, waarop het Pentagon aangaf het aantal troepen in Afrika te verminderen...

Niet

eens een jaar later blijkt er van dit voornemen, troepenvermindering

in Afrika, niets terecht te zijn gekomen....... De VS vecht (dat

vechten wordt ontkend, ondanks alle bewijzen daarvoor, zoals de 4

militairen die in Niger werden gedood) in de volgende Afrikaanse

landen Kameroen,

Kenia, Libië, Mali, Mauritanië, Niger, Somalië en Tunesië...

Vreemd ook dat in het rijtje landen Zuid-Soedan ontbreekt, terwijl ook daar VS militairen opereren....... De president van Soedan, Omar al-Bashir, is bepaald geen vriend van de VS en ondanks dat de VS een wapenembargo heeft ingesteld tegen Zuid-Soedan*, werkt de VS, in het 'niet-zo-geheim', samen met het terreurbewind in Zuid-Soedan.......

Vreemd ook dat in het rijtje landen Zuid-Soedan ontbreekt, terwijl ook daar VS militairen opereren....... De president van Soedan, Omar al-Bashir, is bepaald geen vriend van de VS en ondanks dat de VS een wapenembargo heeft ingesteld tegen Zuid-Soedan*, werkt de VS, in het 'niet-zo-geheim', samen met het terreurbewind in Zuid-Soedan.......

Generaal

Thomas Waldhauser, hoofd Africa Command (AFRICOM), zei tijdens een Pentagon

conferentie afgelopen mei, dat ondanks alle moeilijkheden de VS

militairen hun werk geweldig doen over het hele continent Afrika....... (beter had hij gezegd: dat de VS militairen hun werk uiterst gewelddadig doen, immers het gaat om grootschalige terreur in landen waar de VS niets te zoeken heeft, terreur waarmee de VS zelfs terreur kweekt! Tja als je dat erbij zou zeggen kan je moeilijk volhouden dat de VS goed werk verricht in Afrika....)

Lees

het volgende artikel van Nick Turse, zoals eerder geplaatst op

The Intercept:

U.S. SECRET WARS IN AFRICA RAGE ON, DESPITE TALK OF DOWNSIZING

LAST

OCTOBER, FOUR U.S. soldiers – including two

commandos – were killed in an ambush in Niger. Since then, talk of

U.S. special operations in Africa has centered on missions being

curtailed and troop levels cut.

Press

accounts have suggested that the

number of special operators on the front lines has been reduced,

with the head of U.S. Special Operations forces in Africa directing

his troops to take

fewer risks.

At the same time, a “sweeping

Pentagon review”

of special ops missions on the continent may result in drastic cuts

in the number of commandos operating there. U.S. Africa Command has

apparently been asked to consider the impact on counterterrorism

operations of cutting

the number of Green Berets, Navy SEALs, and other commandos by

25 percent over 18 months and 50 percent over three years.

“Anybody

that knows me knows that I would disagree with any downsizing in

Africa,”

While

the review was reportedly ordered this spring and troop reductions

may be coming, there is no evidence yet of massive cuts, gradual

reductions, or any downsizing whatsoever. In fact, the number of

commandos operating on the continent has barely budged since 2017.

Nearly 10 months after the debacle in Niger, the tally of special

operators in Africa remains essentially unchanged.

According

to figures provided to The Intercept by U.S. Special Operations

Command (SOCOM), 16.5 percent of commandos overseas are deployed in Africa.

This is about the same percentage of special operators sent to

the continent in 2017 and represents a major increase over

deployments during the first decade of the post-9/11 war on terror.

In 2006, for example, just

1 percent of all U.S. commandos deployed overseas were in

Africa –

fewer than in the Middle East, the Pacific, Europe, or Latin America.

By 2010, the number had risen only slightly, to 3 percent.

Today,

more U.S. commandos are deployed to Africa than to any other region

of the world except the Middle East. Back in 2006, there were only 70

special operators deployed across Africa.

Just four years ago, there were still just 700 elite troops on the

continent. Given that an average of 8,300 commandos are deployed

overseas in any given week, according to SOCOM spokesperson Ken

McGraw, we can surmise that roughly 1,370 Green Berets, Navy SEALs,

or other elite forces are currently operating in Africa.

The

Pentagon won’t say how many commandos are still deployed in Niger,

but the total number of troops operating there is roughly the same as

in October 2017 when two Green Berets and two fellow soldiers

were killed

by Islamic State militants.

There are 800 Defense Department personnel currently deployed to the

West African nation, according to Maj. Sheryll Klinkel, a Pentagon

spokesperson. “I can’t give a breakdown of SOF there, but it’s

a fraction of the overall force,” she told The Intercept. There are

now also 500

American military personnel –

including Special Operations forces — in Somalia. At the

beginning of last year, AFRICOM told Stars and Stripes, there

were only 100.

“None

of these special operations forces are intended to be engaged

in direct combat operations,”

said Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security

Affairs Robert S. Karem, while speaking about current troop levels in

Niger during a May Pentagon press briefing on the investigation into

the deadly October ambush. Despite this official policy, despite the

deaths in Niger, and despite the supposed curbs on special operations

in Africa, U.S. commandos there keep finding themselves in situations

that are indistinguishable from combat.

In

December, for example, Green Berets fighting alongside local forces

in Niger reportedly killed

11 ISIS militants in

a firefight. And last month in Somalia, a member of the Special

Operations forces, Staff

Sgt. Alexander Conrad, was killed and

four other Americans were wounded in an attack by members of the

Islamist militant group Shabaab. Conrad’s was the second death of a

U.S. special operator in Somalia in 13 months. Last May, a Navy

SEAL, Senior

Chief Petty Officer Kyle Milliken, was killed,

and two other American troops were wounded while carrying out a

mission there with local forces.

Between

2015 and 2017, there were also at

least 10 previously unreported attacks on

American troops in West Africa, the New York Times revealed in March.

Meanwhile, Politico recently reported that, for at least five years,

Green Berets, Navy SEALs, and other commandos — operating under a

little-understood budgetary authority known as Section 127e that

funds classified programs — have

been involved in reconnaissance and “direct action” combat

raids with

local forces in Cameroon, Kenya, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger,

Somalia, and Tunisia. Indeed, in a 2015 briefing obtained by The

Intercept, Bolduc, then the special ops chief in Africa, noted that

America’s commandos were not only conducting “surrogate” and

“combined” “counter violent extremist operations,” but also

“unilateral” missions.

While

media reports have focused on the possibility of imminent reductions,

the number of commandos deployed in Africa is nonetheless up 96

percent since 2014 and remains fundamentally unchanged since the

deadly 2017 ambush in Niger. And as the June death of Conrad in

Somalia indicates, commandos are still operating in hazardous areas.

Indeed, at the May Pentagon briefing, Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, the

chief of U.S. Africa Command, drew attention to special operators’

“high-risk missions” under “extreme conditions” in Africa.

America’s commandos, he said, “are doing a

fantastic job across the continent.”

Top photo: An American Special Forces soldier trains Nigerien troops during an exercise on the Air Base 201 compound, in Agadez, Niger, on April 14, 2018.

We

depend on the support of readers like you to help keep our nonprofit

newsroom strong and independent. Join Us

*

Volgens de NRC exporteerde de VS al minimaal wapens naar

Zuid-Soedan...... ha! ha! ha! ha! ha! Het is de redactie blijkbaar

nog niet opgevallen dat de VS ook via omwegen een land vol kan

proppen met wapens (zoals de CIA al zo vaak heeft geregeld), desnoods (of zelfs het liefst) aan elkaar

bekampende groeperingen......========================================

De VS heeft meer militaire operaties

in Afrika dan in Midden-Oosten

Hier het tweede artikel van Nick Turse op Vice News, een artikel dat zoals gezegd afgelopen woensdag werd gepubliceerd. Met iets meer actuele informatie. Gezegd moet worden dat Turse bij de aanvang van dit bericht een fout maakt, hij doelt duidelijk op een hinderlaag die in oktober 2017 plaatsvond, terwijl je uit z'n schrijven zou kunnen opmaken dat het om oktober 2018 gaat, in het artikel hierboven wordt ook oktober 2017 aangehaald.

In dit bericht schrijft Turse over het grote aantal militaire operaties die de VS uitvoert in Afrika, operaties die de operaties van de VS in het Midden-Oosten ver overtreffen, al is het aantal VS militairen in het Midden-Oosten veel groter.

Mijn excuus voor de belabberde weergave, krijg het niet op orde.

EXCLUSIVE:

THE U.S. HAS MORE MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFRICA THAN THE MIDDLE EAST

The

deadly ambush in Niger last October that left four U.S. serviceman

dead prompted months of hand-wringing inside the Pentagon. But that

botched operation, which drew national attention to U.S.

counterterror operations throughout Africa should not have shocked

military leadership, the former commander of U.S. Special Operations

forces in Africa told VICE News.

“These

weren’t the first casualties, either. We had them in Somalia and

Kenya,” said retired Brig. Gen. Donald Bolduc, who served as

commander of Special Operations Command Africa (SOCAFRICA) from April

2015 to June

2017,

in an interview with VICE News. “We had them in Tunisia. We had

them in Mali. We had them in Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Chad. But

those were kept as quiet as possible. Nobody talked about it.”

Indeed,

two separate military efforts — named Juniper Shield and Obsidian

Nomad — that were set

to intersect but failed to

on the night of the deadly ambush near Tongo Tongo in Niger were part

of a pattern of expansion on the African continent that has made it

the most active U.S. military theatre in the world. The United States

has conducted more than 30 named operations and activities in Africa

over the last three years, according to documents obtained by VICE

News. While more troops are deployed to, and engaged in combat in,

the Greater Middle East, the sheer number of named efforts in Africa

actually surpasses that region.

VICE

News reviewed documents from the U.S. Army, Africa Command, and

Special Operations Command Africa, and conducted interviews with

current and former military personnel and experts familiar with

America’s “war on terror” in Africa. These documents and

testimony paint a startling picture of a sprawling, labyrinthine, and

at times chaotic shadow war on the African continent, in which

commandos are endangered by a lack of resources and “assistance”

operations blur with combat.

“Africa

has more named operations than any other theater, including CENTCOM

[the command that oversees the Middle East],” Buldoc confirmed to

VICE News. “But remains under-resourced for doing what it’s been

directed to do.”

SECRETIVE AND SPRAWLING

In

2017, U.S. troops carried out an average of nearly 10 missions per

day —3,500

exercises, programs, and engagements for the year —

across the African continent, according to Gen. Thomas Waldhauser,

the AFRICOM commander.

These

efforts — carried out in at least 33

countries —

range from capture-or-kill commando raids to more banal training

missions. Americans are also gathering intelligence, involved in

surveillance and reconnaissance missions carried out by drones,

engaged in construction projects, and accompanying allies on tactical

operations.

There

are also now 34

U.S. military outposts on

the continent, concentrated in the north and west and the Horn of

Africa, according to a recent report by The Intercept.

This

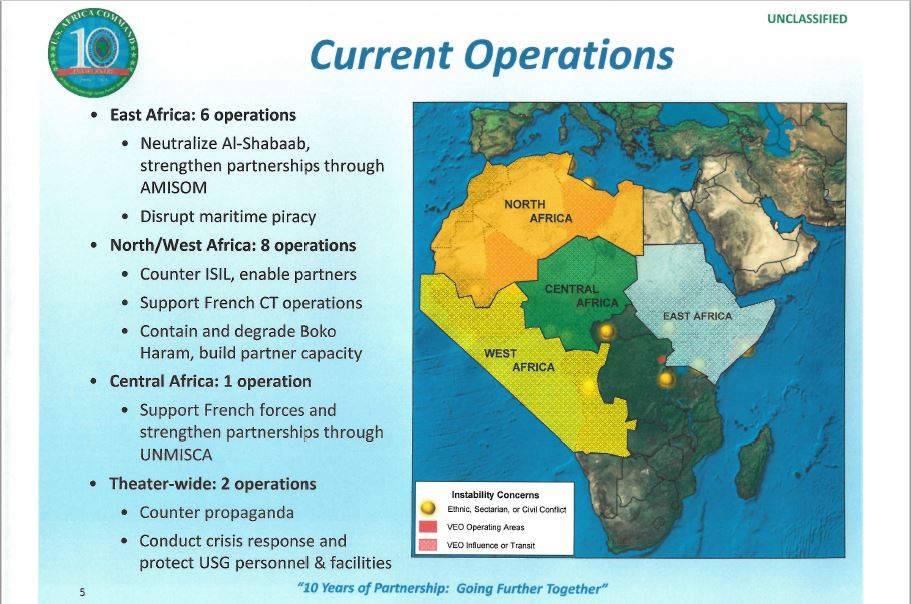

March 2018 briefing authored by Africa Command Science Advisor Peter

Teil outlines current U.S. military operations throughout the African

continent. (Nick Turse for VICE News).

Through

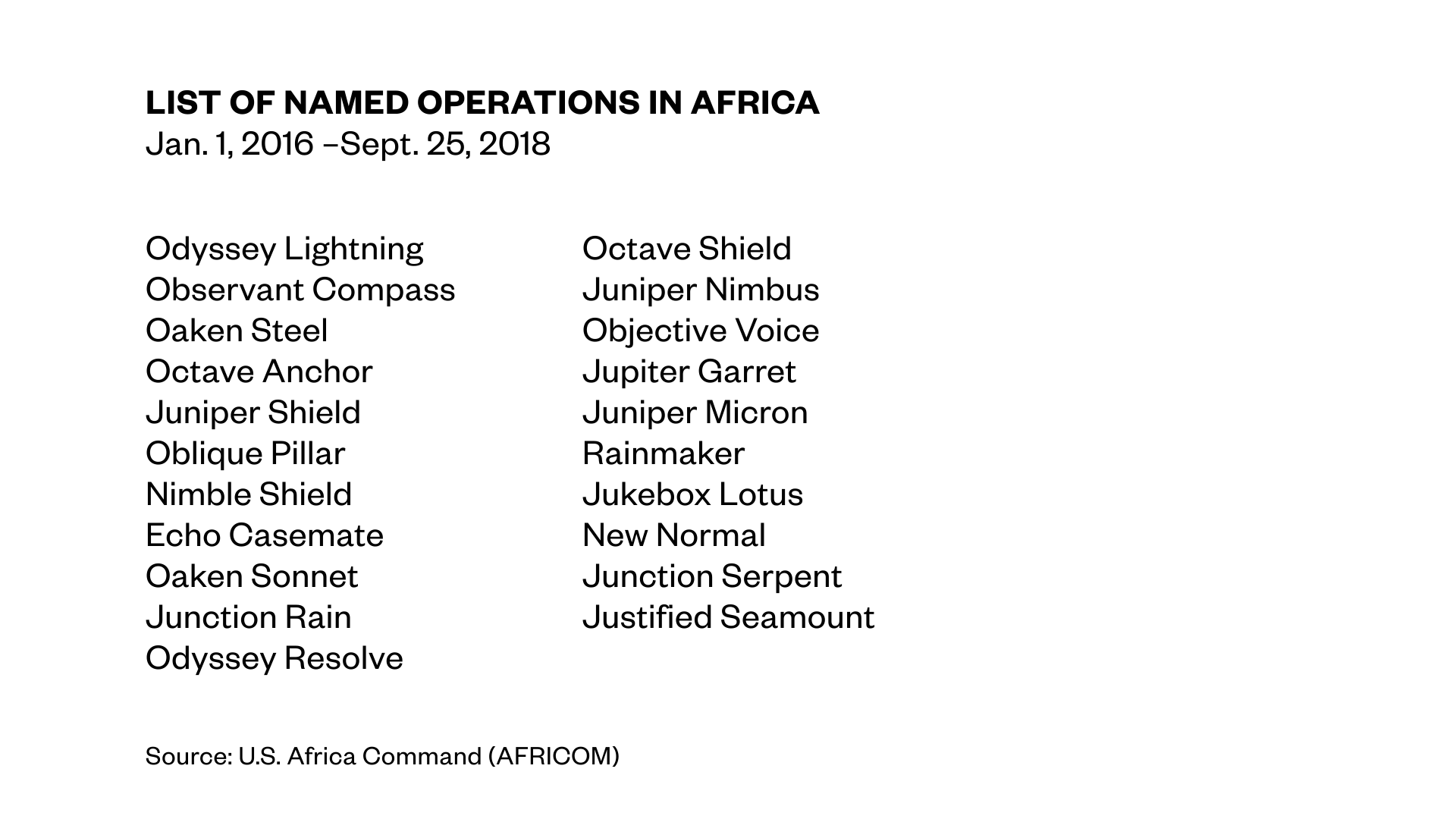

the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), AFRICOM provided VICE News

with a list of 21 named operations conducted between January 1, 2016

and September 25, 2018. According to a separate March 2018 briefing,

authored by Africa Command Science Advisor Peter Teil and also

obtained via FOIA, eight current operations in North and West Africa

were aimed at countering the Islamic State and Boko Haram and

assisting local allies and French counterterrorism efforts. Six

operations in East Africa focused on defeating al Shabaab, assisting

the African Union Mission in Somalia, and counter-piracy. Two

theater-wide efforts focused on crisis response in the event U.S.

government personnel or facilities are threatened, while one

operation — Echo Casemate — provides support to French and U.N.

forces in the troubled Central African Republic.

A

separate Defense Department document, marked “For Official Use

Only,” that appears to have been posted online inadvertently, lists

12 named activities not on AFRICOM’s list, including eight in the

east and another four in the northwest.

Taken

together, these documents represent the most current and complete

record of named U.S. operations and activities recently conducted on

the continent, offering a window into a collection of

little-understood, often overlapping, military efforts unknown to

most Americans.

SPREAD THIN, AND BLURRING LINES

Somali

soldiers are on patrol at Sanguuni military base, where an American

special operations soldier was killed by a mortar attack on June 8,

about 450 km south of Mogadishu, Somalia, on June 13, 2018. - More

than 500 American forces are partnering with African Union Mission to

Somalia (AMISOM) and Somali national security forces in

counterterrorism operations, and have conducted frequent raids and

drone strikes on Al-Shabaab training camps throughout Somalia.

(MOHAMED ABDIWAHAB/AFP/Getty Images).

The

proliferation of so many concurrent counterterrorism efforts courts

danger, said Bill (William) Hartung, the director of the Arms and Security

Project at the Center for International Policy (ASPCIP).

“Running

so many operations with combat implications without making them known

to the American public is both unwise and ultimately undemocratic. It

is no way to run foreign policy in a democracy,” he said. “And

running sensitive operations that are secret, or simply not widely

publicized, increases the risks of failure, because they are not

subject to public debate or adequate scrutiny.”

Bolduc

also criticized the lack of transparency on the part of AFRICOM.

“What we’re doing shouldn’t be a mystery,” he said.

Alice

Hunt Friend, the principal director for African affairs in the Office

of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy from 2012 to 2014, said

the risks are compounded by the way these operations tend to blur

between “assistance” and combat.

“If

the primary military activity in a country is assistance, then as we

saw in Niger, U.S. combat-related resources are not readily on hand,”

Friend explained.

Among

the operations that provide “assistance” are the classified 127e

programs. These secretive efforts are “aimed at assisting foreign

forces who support U.S. counterterrorism operations,” said Friend.

But

these activities often consist of far more than assistance, said

Bolduc. Classified 127e programs are “direct action” efforts,

which are defined by the Pentagon as “short-duration strikes and

other small-scale offensive actions conducted as a special operation

in hostile, denied, or diplomatically sensitive environments.”

Such

direct-action missions were carried out in Cameroon, Kenya, Libya,

Mali, Niger, Somalia, and Tunisia in recent years, as well as two

nations where the 127e programs have now ended, Ethiopia and

Mauritania, said Bolduc.

Through

the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), AFRICOM provided VICE News

with a list of 21 named operations conducted between January 1, 2016

and September 25, 2018. Above is the list. (Nick Turse for VICE

News.)

The

Department of Defense declined to provide details about these

activities because many were “ongoing,” said Navy Commander

Candice Tresch, a Pentagon spokesperson.

“We

are extremely lucky that there have not been more situations like

Niger,” said Hartung. “Running dozens of missions where U.S.

troops are liable to be thrust into combat roles is an extremely

risky approach, putting both their lives and our interests at risk.”

Buldoc

expressed particular concern over what he explained was a persistent

lack of support from the Pentagon. “When I left command, I had 96

missions and 886 tasks associated with those missions in 28 different

countries, in an area that was two and a half times the size of the

United States,” Bolduc said. “I was under-resourced in personnel

recovery. I was under-resourced in ISR [intelligence, surveillance,

and reconnaissance assets]. And I was under resourced in medical

support — the three key things that I needed.”

For

years, the special operations community and its supporters have

expressed concern over deployment

rates, operations

tempo, and the amount of resources being allocated to direct action

missions. “Most SOF units are employed to their sustainable

limit,” General

Raymond Thomas (III), the Special Operations Command chief, told members of Congress last

spring.

In

June, the New York Times reported that Secretary of Defense James

Mattis and Gen. Joseph F. Dunford Jr., the chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, had grown concerned that commandos across the globe

were spread

too thin.

And the resources afforded to the team ambushed in Niger in 2017, for

example — who relied on contracted medical evacuation services,

French airpower, and lightly armored vehicles — have been

criticized as inadequate and dangerous.

Bolduc,

the former SOCAFRICA commander, laid much of the blame of the Niger

ambush on such deficits and a failure to adequately support local

allies. “That lack of resources — as well as fundamentally

misunderstanding the environment, the situation, and the threat —

meant that we were unable to help our partners solve a regional

problem. Because we didn’t provide an adequate military and

security response, the threat got stronger and more effective. The

direct result was the ambush of our SOF team in October 2017.”

Africa

Command's official investigation, however, concluded that the “direct

cause of the enemy attack in Tongo Tongo is that the enemy achieved

tactical surprise there, and our forces were outnumbered

approximately three to one,” according to AFRICOM’s former chief

of staff, and now the head of the U.S. Army in Africa, Maj. Gen.

Roger Cloutier.

DRAWING DOWN — SORT OF

The

Pentagon told VICE News that the total number of troops assigned to

AFRICOM — about 7,200 personnel — would be cut by less than 10

percent over several years, as it reviews its priority areas on the

continent and reorients itself toward great power rivals.

There

are, by comparison, roughly 24,000

troops deployed

to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, although President Trump recently

suggested that U.S. troops might be withdrawn from

the Middle East due to lower oil prices.

President

Donald Trump with, from left, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, Trump,

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford and Marine

Corps Commandant Gen. Robert Neller, speaks during a briefing with

senior military leaders in the Cabinet Room at the White House in

Washington, Tuesday, Oct. 23, 2018. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

Pentagon

spokesperson Tresch said that the ambush in Niger had nothing to do

with the Defense Department’s decision to modestly decrease troop

levels in Africa. She said the move is predicated on the National

Defense Strategy,

released earlier this year, which calls for increased focus on

near-peer competitors. The Trump administration is reportedly poised

to unveil a broader strategy

for Africa specifically

focused on countering the influence of Russia and China on the

continent.

“As

we prioritize where we need to place concentrations of troops, there

were certain specialties — especially in the Special Operations

arena — that we didn’t necessarily need employed in Africa,”

AFRICOM’s Senior Enlisted Leader Chief Master Sergeant Ramon

Colon-Lopez told

VICE News.

Few,

if any, troops will be cut from hotspots like Libya and Somalia, nor

Djibouti, whose bases also play a pivotal role in U.S. operations in

Yemen and the greater Middle East. Nor will any region of the

continent see all U.S. forces removed. Troop drawdowns in West Africa

will be marked by a shift from tactical-level support to a greater

emphasis on advising, training and intelligence-sharing, the Pentagon

said.

Bolduc,

who supports robust military and diplomatic engagement on the

continent, warned that any significant cuts to special operations

forces would irreparably harm U.S. interests in Africa.

“We’re

becoming risk averse and it’s slowing down the amount of support we

provide to our partner nations in training, advising, assisting, and

accompanying them,” he said. “We’re basically ceding our

strategic leverage and relationship with our African partners to the

Chinese and the Russians.”

But

Friend said there was greater risk in small teams of special

operators conducting far flung and secretive missions on the

continent.

“The

fact that American forces were out in the field like that made them

vulnerable to [ISIS in the Greater Sahara] attacks. If they’re not

forward and not out there, it’s much harder to attack them,” she

said. “So, one of the choices in front of DoD decision-makers is

‘do we want to keep forces forward?’ and therefore ‘what kind

of support do we need to give them?,’” Friend said.

Cover

image: Malian soldiers take part in training at the Kamboinsé

general Bila Zagre military camp near Ouagadougo in Burkina Faso

during a military anti-terrorism exercise with US Army instructors on

April 12, 2018. (ISSOUF SANOGO/AFP/Getty Images)

==================================Zie ook:

'VS vermoordt zoals gewoonlijk straffeloos burgers in geheime Somalische oorlog'

'VS bombardementen: 62 vermoorde stadsbewoners in Somalië'

'De VS heeft 500 militairen ingezet in Somalië, het imperium breidt zich verder uit......'

'VS illegaal militair ingrijpen in Niger, ofwel de uitspattingen van een imperium met expansiedrift'

'VS 'helden' helpen Somalische troepen bij het vermoorden van kinderen, één van de specialiteiten van deze helden..........'

'VS 'helden' helpen Somalische troepen bij het vermoorden van kinderen, één van de specialiteiten van deze helden..........'

'Jeroen Leenaers (CDA): Somalië is 'veilig' voor vluchtelingen.............' en in het verlengde daarvan: 'Jeroen Leenaers (CDA EU): 'veilige landen' moeten asielzoekers terugnemen, anders zwaait er wat........ OEI!!!' en: 'Amnesty International beschuldigt Nederland van het schenden van de mensenrechten, door Somaliërs terug te sturen......'

'VS, in 2016 vermoordde de VS 24.000 mensen, uit landen die op de lijst van inreisverboden staan.......'

'VS pleegt aanslag op een leider van al-Shabaab, geen 'onschuldige slachtoffers.....''